Co-consciencia. Referencias

Entender la consciencia como un espectro es vital para entender el TID, y en este artículo demostraremos que se ha discutido este fenómeno en la bibliografía de disociación traumática.

El elemento característico del Trastorno de Identidad Disociativo es la existencia de dos identidades suficientemente autónomas, con su propio sentido de identidad distinto, que alternan la consciencia y el control ejecutivo. Es decir, una puede estar consciente (“aware”) mientras la otra no lo está. Ambas pueden llevar la vida diaria. Es el elemento clave del TID. Pero hay mucho más allá de eso.

La co-consciencia es un término acuñado por Morton Prince en 1906 cuando encontró que “subconsciente” era un término que no se ajustaba al fenómeno de dos consciencias concomitantes, refiriéndose a una de las partes de Christine Beauchamp, su paciente con TID.

Digamos que tenemos la identidad A, y la identidad B.

A puede irse a dormir, pero justo cuando pensó que iba a dormir, B se levanta, consciente de que A iba a dormir, y se decide mirar televisión porque tiene miedo de dormir.

A se despierta en el sofá con la televisión encendida.

A no sabe cómo llegó al sofá. Siente que no ha dormido.

En este ejemplo, A no estaba consciente cuando B estaba consciente, pero B sí estaba consciente de A.

A vivió un blackout (laguna mental, apagón, tiempo perdido).

B estaba co-consciente. A no lo estaba.

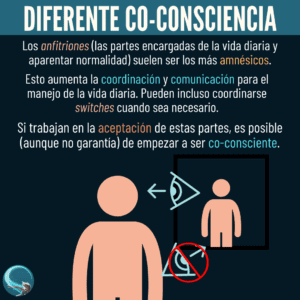

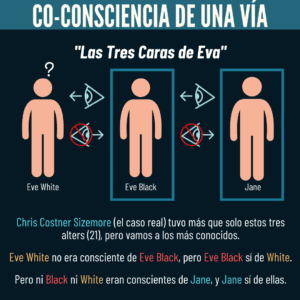

Lo anterior es la co-consciencia de una vía. (También se puede llamar amnesia de una vía).

La co-consciencia de dos vías sucede cuando A y B están conscientes de la presencia de la otra, al mismo tiempo, y pueden experimentar lo que se vive al mismo tiempo. Ambas podrían estar comiendo un pastel y lo experimentarían de distintas formas.

En personas que no tienen partes disociadas estructuralmente, estaríamos hablando de algo similar a la meta-consciencia o «el yo observador».

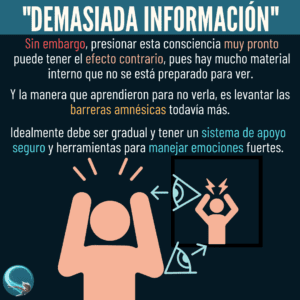

El sistema de partes en una persona con TID puede tener diferentes grados de amnesia, barreras amnésicas y co-consciencia. Y esto puede cambiar a lo largo de la vida. Las barreras amnésicas pueden crecer o volverse porosas entre distintos grupos de alters.

Las barreras amnésicas entre alters son mecanismos automáticos, pero que pueden resistirse o promoverse. Existen alters que se formaron para resistir esta necesidad emocional de separarse por completo, por ejemplo, para estar siempre alerta de peligro. Hay algunos tipos de alters que se vuelven intérpretes, administradores y mensajeros entre alters que no saben qué está sucediendo.

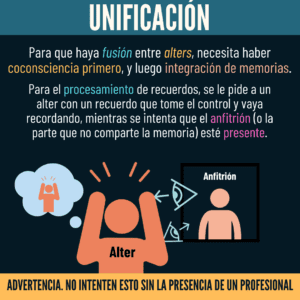

Lo más importante de recordar es que la co-consciencia no solo es posible, sino que la integración de memorias, fusión entre partes y la unificación no puede suceder sin co-consciencia.

Un alter no puede integrar una memoria si nunca está presente al mismo tiempo que el alter que la vivió.

A continuación presentamos muchas referencias bibliográficas.

Nota: Como no muchas referencias usan el término co-consciencia, agregaremos referencias que sugieran el concepto como: el diálogo, coordinación, comunicación, consciencia de las partes (awareness), cofronting (o estar en control al mismo tiempo), co-presencia, o procesos mentales de hacer consciencia de distintas partes del self/yo.

Referencias:

—1

2. in cases of dissociative identity disorder, a person’s sense of having access to coexisting, distinct personalities. —coconscious adj. [described by U.S. physician Morton Prince (1854–1929), who preferred coconscious to the term subconscious]

—2

Although B I and B IV as personalities were not subconscious— in the sense in which this term is used in this study — to each other, yet certain isolated, disconnected, «scrappy» memories of each sometimes persisted and formed a coconsciousness to the other.

…

Another use of the term is to define those perceptions and mental states of which we are only partially aware at any given moment, and which may figuratively be said to lie in the fringe of the focus of consciousness.

This, of course, is equivalent to coexistence. After all, it is only a matter of definition, but we must have some term to designate coexistent dissociated thought, and this seems to be the natural meaning of » subconscious ; » that is, something that at the moment actually streams under the primary consciousness. A much better term for such thought is, a » co-consciousness » or » concomitant consciousness,» but the conventional term has become so widely accepted that the best we can do is to limit its meaning.

Prince, M. (1906). The dissociation of a personality: A biographical study in abnormal psychology. Longmans, Green and Co. https://doi.org/10.1037/10006-000

—3

It is interesting to note that the introspective observations of B agree in principle with those in the account given by the coconscious personality in the case of Miss Beauchamp.

…

As an alternating personality I (B) remember both states and my own coconscious life, but not the hypnotic states. When I am coconscious (with A and C), however, I remember my own hypnotic state and A’s, but not C’s hypnotic state.

A, B. C. (1909). My life as a dissociated personality.

—4

The development of internal cooperation and co-consciousness between identities is an essential part of Phase 1 that continues into Phase 2. This goal is facilitated by a consistent approach of helping DID patients to respect the adaptive role and validity of all identities, to find ways to take into account the wishes and needs of all identities in making decisions and pursuing life activities, and to enhance internal support between identities.

…

Early in the treatment, therapists and patients must establish safe and controlled ways of working with the alternate identities that will eventually lead to co-consciousness, co-acceptance, and greater integration.

Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation. Guidelines for Treating Dissociative Identity Disorder in Adults, Third Revision. 2011

—5

Una dificultad común al principio es la aparición de amenazas internas cuando trata de comunicar con partes suyas. Habitualmente proceden de una parte muy dominante y crítica. Dichas partes, como se expuso en capítulos anteriores, solo están intentando protegerle reaccionando con los patrones rígidos y limitados de respuesta que conocen. Estas partes necesitan ayuda para aprender formas más eficientes y empáticas de proteger y tratar con el miedo, la cólera y la vergüenza. Lo más fácil es empezar, si es posible a dialogar con una parte con la que se sienta más cómodo.

Boon, Suzette/Steele, Kathy/Van der Hart, Onno. Vivir con disociación traumática. Dessclée De Brouwer.

—6

Awareness of the presence of other personalities has been widely reported in the empirical literature on DID [16–20,24,25,27,32,35]. Such awareness is a common occurrence in DID. Moreover, many patients who have DID hear or see what some personalities say or do when they are ‘‘out.’’ Many clinicians have incorrectly assumed that a person who has DID can never be aware of the activities of another personality

Dell, P. F. (2006). A new model of dissociative identity disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29(1), 1-26. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2005.10.013

—7

Dada la alta carga traumática del evento y que no hubo nadie que se diese cuenta o a quien pudiese contarlo, el evento traumático nunca fue asimilado ni integrado. La parte que se quedó sintiendo la experiencia – con toda su carga de dolor y angustia – y la parte que se desconectó nunca volvieron a reunirse, a experimentar a la vez ninguna experiencia, a tener lo que denominamos coconsciencia.

Anabel González; Dolores Mosquera. Trastorno de identidad disociativo o personalidad múltiple (p. 100)

—8

For Mitchell (1922), that which is dissociated always resides in another part of the personality. Discussing Janet’s dissociation theory, he wrote:

…But if its passage out of consciousness is accompanied by dissociation, it may continue to exist as an unconscious psychical disposition or as a coconscious experience, and forms an integral part of some personality which may or may not be wider than that which manifests in waking life. (p. 113/4, emphasis added)

…

Clinical work with dissociative children demonstrates that, unlike their adult counterparts with DID, they often have coconsciousness and are able to self-observe the changes in behavior that they attribute to imaginary friends or other selves, a seemingly rather sophisticated metacognitive achievement.

…

Experience with early forms of dissociative disorders in children suggest that DID adults who do not have coconsciousness and demonstrate primitive and segregated self states may have evolved into this extreme form of complex pathology over time through a complex interplay of interpersonal, emotional, and cognitive factors.

…

The alters may be few or many, of various ages, including older than the body, same- or cross-gendered, hetero- or homosexual, alive or dead, with either or both coconsciousness and copresence to varying degrees, which may not be commutative (i.e., may be one-way), communicating not at all, or through hallucinations, or through direct thought transfer, manifesting different physiological signs in the body when out, clustered in various arrays of dyads, subgrouping, layers, purposes, and so on. Subhuman, animal, or imaginary alters are not uncommon, with likely links to children’s fantasy. When out, a given host or alter may appear globally to be mentally and behaviorally whole and normal or an exaggerated caricature or a single-function agent, and so on, but not necessarily congruent with the age and gender of the body.

Dell, P. F. (2009). Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders. DSM-V and Beyond. Taylor and Francis. Edición de Kindle.

—9

As I met and built a trusting relationship with each alter and validated each one’s story, the boundaries between ego states became less rigid and psychic energy became more fluid. My client became aware of the other parts of herself(see Figures 2 and 3).

Hudson, S. (2000). Working with Dissociative Identity Disorder Using Transactional Analysis. Transactional Analysis Journal, 30(1), 91–93. doi:10.1177/036215370003000110

—10

In Table 3 we can observe that the Puerto Rican alters are very similar to the ones reported by Coons et al. (1988); Putnam, et al. (1986); and Ross, et a!. (1989). Most of them have idiosyncratic tones of voices (80%), different handwriting styles (53%), report co-conscious states (80%), and, at times, are amnestic of others (73%).

Martinez-Taboas A. Multiple personality in Puerto Rico: analysis of fifteen cases. Dissociation 1991; 4(4):189–92.

—11

The choice of stance and selection of techniques often will be made in connection with a study of the patient’s ego strength, track record, character style, and an appreciation of what tasks often accomplished by techniques can be accomplished deliberately by the alter system. For example, a very strong DID patient with good accessibility to alters upon request and good capacities for coconsciousness might be treated from a strategic integrationalist stance in a psychodynamic psychotherapy with only a few modifications. A similar patient with less certain accessibility to alters upon request and with poor capacities for coconsciousness might be treated from the same stance and with the same basic modality, but it would be anticipated that another modality, such as hypnosis, would be a useful adjunct in addressing the less certain accessibility and the problematic coconsciousness.

Kluft, R. P. An overview of the psychotherapy of dissociative identity disorder. Am J Psychother. 1999 Summer;53(3):289-319. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1999.53.3.289. PMID: 10586296.

—12

The result is that many people who have these parts do not recognize the muscle movements, or visual or auditory intrusions, as behavior caused by parts. Other people might have coconscious parts or parts that run the body. It can get complex (see Appendix II).

…

These dissociated memories, which include behavior, can form dissociative parts. These dissociated parts can give intrusions that run the body like a skill, coconsciously, with the Main Personality.

Flint, G. (2014). A theory and treatment of your personality.Neosolterric Enterprises

—13

The development of internal cooperation and co-consciousness between personalities is an essential part of early phase treatment that then continues into the middle phase. The therapist must emphasize the adaptive role and validity of all personalities and encourage the host to find adaptive ways to accommodate the wishes and needs of all personalities.

Chu, J. A. (2011). Rebuilding shattered lives: Treating complex PTSD and dissociative disorders (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118093146

—14

“Standing Behind My Eyes”

Far more common is the experience of co-consciousness: having one part in control of speech and actions while one or more other parts, often including the host, are watching and listening, but helpless. Ellie describes coconsciousness as “standing behind my eyes unable to control what’s going on, but I can hear and I know what’s happening.”…

When Elizabeth was switched but remained co-conscious, she would sometimes notice her mouth twitch, then hear that her speech had changed in tone, volume, or pronunciation. Over

Hyman, J. W. (2007). I am more than one: How Women with Dissociative Identity Disorder Have Found Success in Life and Work. McGraw Hill Professional.

—15

How coconscious patients are also varies—that is, the extent to which they have knowledge of and are privy to the thoughts, history, and affairs of the other parts varies. Often, the part of the self that is in executive control is unaware of the thoughts and activities of other parts (often called one-way amnesia). However, this is a tricky topic to try to make clear. For example, coconsciousness may be minimal before beginning psychotherapy for DID but tends to increase considerably in the course of appropriate psychotherapeutic work. Although parts other than the part who is most often in executive control (often called the “host”) are more likely to know of each other and of the host, this is not always the case and is not always the same for different parts of the same patient. Some parts may be unknown by many of the others. The dissociative structure of each patient is different.

Howell, E. F. (2011). Understanding and treating dissociative identity disorder: A relational approach. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

—16

The third personality was «Sally,» mischievous, breezy, and irresponsible. Sally was always coconscious with the other personalities and, according to Prince, was made up of fragments repressed from the main consciousness during childhood.

…

Like Sally, Margaret was coconscious with the other personalities. The fourth, Sleeping Real Doris, was actually a somnambulistic personality who appeared only when Doris was asleep.

Crabtree, A. (1993) Multiple personality before “Eve”. Dissociation : Vol. 6, No. 1, p. 066-073 :

—17

“Wait a minute,” Rikki interrupted. “What exactly are you talking about here, Arly? You mean like Sybil?”

Arly nodded. “In a way, yes,” she said, “although in Sybil’s case her personalities were so separate she would black out completely whenever they came out. I don’t think Cam experiences that. His alters take over to greater or lesser degrees at different times. He’s aware of them when they’re out, and they seem to be aware of each other. That’s called coconsciousness.”

West, C. (1999). First person plural: My life as a multiple. New York: Hyperion.

—18

The second problem is that Prince never clarified what the relation between dissociation and co-consciousness is supposed to be. Sometimes he seems to identify dissociation and co-consciousness — for example, by stating explicitly that ‘extra-conscious’, ‘doubling of consciousness’, ‘coconscious’ and ‘dissociation’ are all synonyms for ‘subconscious’ (1939, p. 354, 481). But at other times Prince writes as if they are distinct. For example, on some occasions, he suggests that co-consciousness accompanies only a high degree of dissociation (1939, p. 69) or that it occurs only when ideas are far outside the focus of attention (1939, p. 215).

Braude, S. E. (1995). First person plural: Multiple Personality and the Philosophy of Mind. Rowman & Littlefield.

—19

Dr. George put his fingertips together. “Because other therapists have tried that in conditions like yours, Billy. And it doesn’t seem to work. The best hope you have of improving is to bring all these aspects of yourself together, first by communicating with each other, then by remembering everything each of them is doing, getting rid of the amnesia. We call that co-consciousness. Finally, you work at bringing the different people together. That’s fusion.”

Keyes, D. (1981). The Minds of Billy Milligan. New York: Bantam Books

—20

I have recently begun talking to my therapist about how the split that exists in my system between host and alters, which was so vital for a time in my life, is not very conducive to moving towards co-consciousness or integrative functioning, as it requires artificially pushing them away when we have to function in the outside world. This is exhausting and can result in a pressure-cooker environment from which they erupt, and is not very representative of how we live. It also denies them the things that they can do and skills they can develop. Not that they should be obviously out if it is not appropriate, but that is different to committing to a postgraduate study that would ask them to go away for large periods of time.

Bowlby, X. and Briggs, D., 2014. Living with the Reality of Dissociative Identity Disorder : Campainging Voices. [ebook] London: Routledge.

—21

Three personalities sat down in our single body in the crowded, noisy bar. Suddenly, and for the first time, Kendra, Isis, and I were co-conscious. All there, at the same time, but still separate. Kendra sipped her beer and squinted at Lynn through the smoke. “OK,” she said, “Renee, Isis, and I are ready to talk about it.”

“Talk about what?” Lynn asked. She seemed confused.

“All three of us are able to listen and talk to one another and to you,” Kendra explained with a trace of impatience. “Treat it like a conference call. Let’s talk about whether or not we should fuse.”

“Kendra, is that you?” Lynn asked.

“Yes, it’s me,” Kendra said, grinning wickedly at Lynn’s surprise. “Remember, you’re the one who started this conversation.”

“It’s me too,” Isis said in her breathy, delicate voice.

“And, by the way,” I added, “it’s me, Renee, too.”

Lynn shook her head in wonder and looked around at the strangers sitting at her elbow. She gulped her beer and plunged into the conversation. “OK, I guess nobody around us will be able to make sense of the discussion anyway.”

Casey, J.F. with Lynne Fletcher (1991) The Flock: The Autobiography of a Multiple Personality. New York: Knopf.

—22

One sign of new professionalism is terminology. We have a prodigious flight of mixed metaphors. To quote from a single recent paper on adolescent multiples (average number of personalities, 24.7): ’detoxifying the environment’, ’fusion’, ’titrating abreactions’, ’metabolizing the trauma’, ’contracting’ (Dell and Eisenhower, 1990). Readers can guess what ’fusion’ means – the ’alters’ are made ’coconscious’ and then fused, i.e. brought together to form one whole person.

Hacking, I. (1992). Multiple personality disorder and its hosts. History of the Human Sciences, 5(2), 3–31. doi:10.1177/095269519200500202

—23

La forma de TID que tengo se caracteriza por lo que se conoce como co-conciencia[3]. Esto quiere decir que hay un “yo” central al que siempre se regresa de esos estados de aislamiento…() Después de haber ganado la fuerza suficiente para saber de estas habitaciones y poder tener acceso al contenido de las mismas, desarrollé una co-conciencia, o una conciencia compartida de todas mis partes para así poder comunicarme.

Trujillo, O. (2019). La suma de mis partes: Testimonio de una Sobreviviente de Trastorno de Identidad Disociativa. Tortuga Publishing

—24

El TID comprende una gama de trastornos que incluyen la disociación y la creación interna de partes para protegerte de un trauma severo. En tu caso, fuiste capaz de mantener un ‘yo’ central que siempre está presente en algún nivel. Este yo central puede estar consciente de tus otras partes. Tus partes también pueden conocerse e interactuar entre sí. Esto se llama co-consciencia”.

Trujillo, O. (2019). La suma de mis partes: Testimonio de una Sobreviviente de Trastorno de Identidad Disociativa. Tortuga Publishing

—25

Good DID therapy involves promoting co-consciousness. With co-consciousness, it is possible to begin teaching the patient’s system the value of cooperation among the alters. Enjoin them to emulate the spirit of a champion football team, with each member utilizing their full potential and working together to achieve a common goal.

Yueng, D. (2020) Engaging multiple personalities volume 4 the collected blog posts.

—26

The patient reported states of coconsciousness with one alter identified as “The Persecutor,” and another as “The Witness,” who was visualized by the patient as “starting off as a body and ending as a fluid substance or brown cloud”…() The patient also experienced the presence of childlike alters of preschool age.

M. Steinberg, Handbook for the Assessment of Dissociation: A Clinical Guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1995.

—27

An essential component of co-consciousness requires knowing who is present (out). This point may seem obvious, but it is crucial.

Parts inside need to be aware of and know who is ‘out’ at all times; they also need to know and be able to identify who they are as well. If asked (by your therapist, or by someone in your DID group—in other words, by someone who has a legitimate need or reason to know), the part who is out needs to know, and be willing to answer the question “Who’s here?” or “Who am I talking with?”

A.T.W. (2004). Got Parts? An Insider’s Guide to Managing Life Successfully with Dissociative Identity Disorder (New Horizons in Therapy)

—28

Many alters are unaware that others exist within the same individual. This is especially true of the host, who at the beginning of treatment commonly denies being a multiple. On the other hand, some alters may know about other alters and actually be acquainted with them, talk with them, or jointly engage in some activity.

This is called co-consciousness. The alters argue with each other, snarl, or console. One alter may be out and yet have another alter yammering away beside the left ear, telling her what a ninny she is. Many therapists try to introduce different alters to each other, believing that thoroughgoing co-consciousness is a necessary step toward integration.

Hacking, I. (1995). Rewriting the soul: Multiple personality and the sciences of memory. Princeton University Press.

—29

Entendemos por coconsciencia «un estado de conciencia en el que una parte de la personalidad es capaz de experimentar directamente los pensamientos, sentimientos, percepciones y acciones de otro álter», según Morton Prince (1906) (citado en Kluft, 1984).

González, A. (2010) Trastornos Disociativos. Ediciones Pléyades.

—30

However, it was further predicted that when two identities capable of mutual awareness (co-consciousness) each focused on a different aspect (i.e. reading or listening) of the divided attention task, performance would be improved compared to the single identity’s dual task performance. These hypotheses were supported and suggest that attentional capacity in DID may be increased if dissociative identities can process different aspects of complex environmental tasks.

Moskowitz, I. Schäfer & M.J. Dorahy, (Eds.), (2008) Psychosis, trauma, and dissociation: emerging perspectives on severe psychopathology

—31

Creating co-consciousness, then, is the process of making these barriers more porous to allow more information crossflow. It involves a lowering of the security clearance threshold and allowing greater access, by more parts, to information. The solution that we came up with was both simple and effective.

Haynes, Jeni; Blair-West, George. The Girl in the Green Dress (pp. 347-348). Hachette Australia. Edición de Kindle.

—32

It also depends on your degree of co-consciousness. If there is a lot of co-consciousness between your front person and the rest of the parts, you might not be able to process memories without the front person coming to know the content. If your front person has developed strength over the years, you might want him or her to know what happened.

Miller, Alison. Becoming Yourself: Overcoming Mind Control and Ritual Abuse. 2014. Karnak.

—33

Until you are able to establish co- consciousness (an awareness of and ability to communicate with the other alters), you are likely to have problems communicating with the others. There are many ways to improve co- consciousness and to decrease the difficulty communicating with your alters, and these will be presented in chapter 5.

…

If you are aware or suspect that DID may be part of your life, then you might have a different goal for therapy, such as learning how to establish coconsciousness with your alters.

…

With your help, your clients can learn strategies to increase coconsciousness and cooperation between alters.

Alderman, Tracy, Ph.D., Marshall, Karen, L.C.S.W. Amongst Ourselves: A Self Help Guide to Living with Dissociative Identity Disorder. 1998. New Harbinger Publications.

—34

One issue might be the degree of communication and co-consciousness between parts thought necessary for one’s definition of functional. While therapeutic work on developing co-consciousness and communication has frequently been promoted by DID therapists, this has only been portrayed as a step along the way towards integration (Kluft, 1993). Rivera’s stance (p. 41 & p. 122) moves towards seeing communication and co-consciousness as a therapeutic end in itself, but still with the goal of developing a functional “I”.

Clayton, Kymbra. (2005). Critiquing the Requirement of Oneness over Multiplicity: An Examination of Dissociative Identity (Disorder) in Five Clinical Texts. E-Journal of Applied Psychology. 1. 10.7790/ejap.v1i2.21.

—35

When EMDR therapy (or other treatments; e.g., hypnotic abreaction) has successfully resolved the traumatic material, the need for the compartmentalization lessens, amnestic barriers between the personality states dissolve, “co-consciousness” increases, and integration can occur.

Shapiro, Francine. Ph.D. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy, Third Edition Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures. 2018. The Guilford Press.

—36

This paper develops the thesis that co-consciousness is not only a feature of severe dissociative syndromes like multiple personality, or of “altered states” of consciousness like hypnosis, but is a universal feature of healthy living… The overriding therapeutic implication is that dissociation can no longer be viewed only like a pathological “entity” to be gotten “rid of,” but as a basic given which we should learn to use more effectively. The treatment paradigm becomes that of taking dissociative phenomena from the realm of the dysfunctional to that of healthy co-consciousness. so that what was once a symptom becomes a skill.

Beahrs, J. O. (1983). Co-Consciousness: A Common Denominator in Hypnosis, Multiple Personality, and Normalcy. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 26(2), 100–113.

—37

Being able to control switching and ‘dissociating’ (by which we mean an altered state of consciousness) is a vital component of that, but is not an end in itself. Developing co-consciousness and collaboration between parts is also important, and it’s true that traumatic memories are only properly metabolised and processed when the front brain is online. But grounding is only one small technique in that entire process: grounding is not the point.

Spring, Carolyn. Unshame: healing trauma-based shame through psychotherapy. 2019. Carolyn Spring Publishing (Huntingdon, UK)

—38

• Help parts develop ongoing awareness (co-consciousness) and cooperation regarding functioning in daily life and the postures and actions that support this functioning.

• Help all parts develop self-compassion as expressed to various parts, and find physical actions that demonstrate compassion.

Steele, Kathy. Boon, Suzette. van der Hart, Onno. Treating Trauma-Related Dissociation: A Practical, Integrative Approach. 2016. W. W. Norton & Company

—39

(2) Co-consciousness does not impair the individuality of personalities. The well-known interrelations of secondary personalities could lead to the inquiry how far any of the witnesses was of independent authority, and how far she simply reflected the memories of another.

Prince, W. F. (1916). The Doris case of quintuple personality. The Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 11(2), 73–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0072650

—40

We find that the «rule of shared responsibility» helps children decrease inappropriate behavior and may help to ultimately increase co-consciousness. We tell the child that «everyone» (child and his or her dissociated parts) is responsible and «everyone» will have to pay the consequences for wrong behavior.

El término coconsciencia se utiliza para describir las experiencias compartidas entre estados del yo y/o partes disociativas y es uno de los aspectos clave en el proceso de integración. Desde la perspectiva de la teoría de los estados del yo, Phillips y Frederick (1995) proponen diferentes etapas en este camino hacia la integración: reconocimiento, desarrollo de comunicación, desarrollo de empatía, actividades de cooperación, sensaciones internas compartidas, coconsciencia y coconsciencia continuada. Está relacionada con el proceso de superación de la fobia hacia las partes disociativas de la personalidad y el conflicto interno. La coconsciencia se explica detalladamente en el capítulo 11.

Mosquera, Dolores. Voces y Partes Disociativas: Un abordaje práctico basado en el trauma. 2020

—42

Disposición para explorar la co-conciencia. De la misma forma que es importante que al terapeuta se le permita acceso al sistema de estados de ego, es igualmente importante que los propios pacientes logren ese acceso. En las primeras etapas de la terapia, este concepto de coconciencia es, en el mejor de los casos, extraño, y en el peor de los casos, imposible de concebir. Por lo general, cuando la co-conciencia comienza se hace bastante evidente. El paciente pudiera decir. «Vi a una mujer extraña preparando la cena en mi cocina anoche.» Esto, naturalmente, conducirá a una discusión sobre quién pudiera ser esa persona. Alcanzar la co-conciencia es un paso de avance enorme en el tratamiento, y el paciente deberá ser felicitado.

—43

Ross (1989) uses the metaphor of a corporate business structure to describe the process of establishing co-consciousness. Bearhs (1982) speaks of symphony orchestra in which the conductor rather than the CEO must insure cooperation and communication within the organization. My multiple patients have referred to their personality systems more often as families.

Rullo, Anthony J. Multiple Personality Disorder. Two Cases in Progress. 1993

—44

The adult (host/functional) alter, who had been moderately coconscious for most of the session, interjected her impression that I seemed overly interested in the abuse experience she had started out describing.

…

The therapist’s sustained interest in the whole person, including recognition of all the separate and coconscious dissociated elements, contrasts favorably with the divide-and-conquer manipulations of the perpetrator and has a cumulative countervailing impact on the patient’s internal bondage and entrapment in silence.

…

Some alter personalities demonstrate more diversity, capacities, and elasticity than others—which is fortunate, because the by-products range from the potential for greater coconsciousness with other part-selves to the potential for greater participation In life and also in the therapy process. But other patients’ alters excel only at specific tasks, functions, or attitudes that sustain the dissociative organization of self, as a result of the defensive development of parallel realities with limited, internal space for the reconciliation of reality with fantasy.

Harvey L Schwartz. Dialogues With Forgotten Voices: Relational Perspectives On Child Abuse Trauma And The Treatment Of Severe Dissociative Disorders 2000

—45

Leonie knew nothing of Leontine or of Leonore. Leontine was coconscious with Leonie and knew her life, but did not know Leonore. Leonore was co-conscious with and knew the lives of both Leonie and Leontine.

Mitchell, T. W. (1922). Medical psychology and psychical research. London: Methuen & Co.

—46

The person will often know parts of herself in detail but only be aware of others as «voices» heard coming from far back in the psyche. As the person progresses through the active phases of MPD therapy, these voices are engaged, take executive control, achieve coconsciousness, and are integrated.

Joan N. Berzoff. Dissociative Identity Disorder: Theoretical and Treatment Controversies. 1995

—47

Now a maturely developed young woman (she had started puberty at age 9), Penni was animated and friendly. She remembered the last visit 2 days earlier, and asked whether she could play with a certain toy that she had enjoyed then. In the interview, she talked about developing her coconsciousness (i.e., the sense that several of her alter personalities were simultaneously present). Still, there were many angry inner voices, and at times she could not think «cause of the noise inside.»

Frank W. Putnam. Dissociation in Children and Adolescents: A Developmental Perspective. 1997

—48

Relating specifically to working with DID and people with very defined parts, Dr. Korn sees herself as constantly doing group therapy with the presenting client. She is always working toward increasing someone’s coconsciousness and to bring parts into communication, observing that “People need help with scooping up and then stitching together the components of experience.” Dr. Korn maintains that the therapeutic relationship is everything in terms of creating a safe container for the work between the provider and their client. This relational container is essential for undoing the aloneness, and offering co-regulation that allows people to be courageous enough to approach the material that’s been unapproachable.

Jamie Marich. Dissociation Made Simple: A Stigma-Free Guide to Embracing Your Dissociative Mind and Navigating Daily Life. 2023.

—49

If dissociation is unformulated experience, how do we understand dissociative identity disorder, in which large aspects of experience or self-states are dissociated from each other, but appear to be consistent within themselves and to be “formulated experience” from that perspective? My answer is that this apparent formulation is only true from the perspective of an outside observer; these dissociated self-states (“not-me”) are unknown by “me.” They are unformulated by at least some other self-states, quite often including the host. Certain self-states or alters are more coconscious, aware of, and in communication with others; in that case they are relatively more formulated, each to the other, than those that are amnestic of the others’ activities.

Elizabeth F. Howell. The Dissociative Mind. 2013

—50

‘This is really significant, Patricia,’ the professor said. ‘You might say you are the gold standard for DID!’ he smiled. ‘You are one hundred per cent not coconscious.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘It means there is absolutely no seepage between personalities. The majority of dominant personalities in people with DID have some level of awareness of the other alters. Some hear voices, some can see what’s going on when they’re not in control. Some can even talk to all the different personalities in their head.’

‘I can’t do that.’

‘No,’ he agreed. ‘It’s remarkable, isn’t it? I’ve never met anyone like you.’

Noble, Kim. All of Me: How I learned to live with the many personalities sharing my body. 2012

—51

At other times I can’t or I don’t pull back from the brink, and I disappear inside. If I’m aware of it, it’s like falling into sleep or an anaesthetic. Sometimes, when I’m inside, deep, deep down inside myself, I can see what’s happening still on the surface. But I’m watching it from afar, and it’s not me I’m watching. This is co-consciousness, the strangest feeling in the world. I can see myself talking and interacting and doing and feeling, and yet it’s not myself, it’s just someone else, someone I don’t know, someone I have no connection with. And what they do and what they say surprises me.

Spring, Carolyn. Recovery is my best revenge: My experience of trauma, abuse and dissociative identity disorder (p. 70). Carolyn Spring Publishing. Edición de Kindle. 2016

—52

Facilitation of Coconsciousness

Hypnosis can be used to facilitate coconsciousness, which most authorities believe to be a necessary precondition for successful fusion/integration, as well as being extremely important in promoting day-to-day cooperation within an unintegrated multiple personality system.

Putnam, Frank. W. Diagnosis and treatment of multiple personality disorder. 1989

—53

For this intervention to be safe, organized, and therapeutic, however, it is generally accepted that the client must sufficiently exhibit “coconsciousness”; that is, be capable of “listening” to what each part of herself is expressing in each of the two chairs. The intervention is less safely conducted if there is little co-consciousness such that, for example, when the client occupies the voice’s chair, she fully assumes that role as her “singular self,” thereby becoming so fully absorbed in the exercise that she loses concomitant awareness of the perspective that occupied the previous chair

Paul Frewen, Ruth Lanius, Bessel van der Kolk M.D., David Spiegel. Healing the Traumatized Self: Consciousness, Neuroscience, Treatment. 2011

—54

The important tasks in the fi rst phase of therapy are development of coconsciousness of ego states, providing orientation to the present, and affect management.

…

This occurs because the alter personalities are not capable of coconsciousness due to the psychodynamics that govern the self system.

Forgash, C., & Copeley, M. (Eds.). (2008). Healing the heart of trauma and dissociation with EMDR and ego state therapy. Springer Publishing Co.

—55

Yet this total unawareness is by no means the only, and perhaps not the commonest, feature of multiples’ interself epistemology. We must look also at the notion or notions of «coconsciousness.»

The term ‘coconsciousness‘ has been the bearer of several different meanings since its introduction by Morton Prince in his early case descriptions of multiple personalities (Prince 1906, Beahrs 1983). Because of the ambiguity the term carries, we might begin by rehearsing Stephen Braude’s (1991) understanding and definition of ‘coconsciousness‘ and associated terminology.

On Braude’s taxonomy, self A is said to be coconscious with self B when one of two states obtains between the two selves. A may be «cosensory» with B or «intraconscious» with B. A is cosensory with B when both A and B seem to be simultaneously aware of external events, such as sights and sounds. A is intraconscious with B when A claims knowledge of B’s mental states, such as feelings, beliefs, and memories.

Radden, Jennifer. Divided minds and successive selves. Ethical issues in disorders of identity and personality. 1996

—56

In one-way amnesic relationships, the most common relationship pattern, some subpersonalities are aware of others, but the awareness is not mutual. Those who are aware, called coconscious subpersonalities, are «quiet observers» who watch the actions and thoughts of the other subpersonalities but do not interact with them. Sometimes while another subpersonality is present, the coconscious personality makes itself known through indirect means, such as auditory hallucinations (perhaps a voice giving commands) or «automatic writing» (the current personality may find itself writing down words over which it has no control).

Comer, Ronald J. Fundamentals of abnormal psychology. 2016

—57

For example, one woman in her twenties reported sexual abuse by a baby-sitter between ages eleven and thirteen that did not involve intercourse. She had one alter personality with whom she was almost fully coconscious, and she accepted the fact that the alter personality was a part of her without difficulty. Complex inpatient cases, in comparison, often resist accepting the fact that their alter personalities are part of themselves.

Ross, Colin A. Schizophrenia : innovations in diagnosis and treatment. Dissociative Identity Disorder. 2004

—58

In recent years, research such as that by Nissen, Ross, Willingham, MacKenzie, and Schacter (1988) has shown that even in patients who suffer from full-blown DID, the dissociations between implicit and explicit memory stores of normal and dissociative states, and among the stores of different dissociative states, are not absolute; some degree of coconsciousness among different ego states is common.

Van der Kolk, Bessel A., McFarlane Alexander C., Weisaeth, Lars. Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society. 1996

—59

Whenever possible, the alters need to become coconscious and then copresent. If you’ll remember, coconsciousness is the ability of an alter to observe and remember what another alter is doing when that second alter is out. There is an awareness of the other’s thoughts and behavior. Copresence takes this ability one step further—an alter not only understands what the other is thinking but influences the other’s behavior. They are not fused, but they are present as two different personalities simultaneously; they are able to think and act out together.

…

Coconsciousness: The ability of one alter personality to know the thoughts, feelings, or behavior of another alter.

Clark, T. A. (1993). More than one. Thomas Nelson Publishers.

—60

Powers proposed four types of mind: (i) a unitary self-construct, (ii) a self-construct in which significant concerns are split off, (iii) a multiple self-construct in which selves are coconscious, and (iv) a multiple selfconstruct in which different selves take turns to dominate conscious experience.

Lester, D. (2017). On multiple selves. Routledge.

—61

Some personalities are present and “listening in,” while others are out and evident to people who may interact with the multiple. One patient explained that, when coconscious, “it’s like sitting in the back seat, someone else is driving, and I’m in the car” (Del Amo interview).

…

When neither out nor coconscious, it is as if alters are nonexistent, much like the angry or greedy parts of Katherine that, at any given time, lie dormant. Second, alters appear to have access to one another’s mental states in a way that people do not, although parts of the same person may.

Saks, E. R., & Behnke, S. H. (2000). Jekyll on trial: Multiple Personality Disorder and Criminal Law. NYU Press.

—62

When | was about 28 years old or so, and near the beginning of my effort to be coconscious as an adult, | remember searching the cupboards and not finding anything to eat that met the standards of my discerning palate, namely, Cheetos, pudding and vodka.

…

That being said, if you switch to an alter who doesn’t have co-consciousness with the other alters, and they were triggered to come out by something traumatic, they might not have the knowledge or ability to act like who was just out.

…

When a person with a Dissociative Disorder has more than one personality “out” at a time, it’s called Co-consciousness. Throughout my life, I’ve experienced co-consciousness about half the time, sometimes more successfully than others.

Crawford, L. P. (2017). Not otherwise specified: A Multiple Life in One Body, 15 Year Anniversary Edition.

—63

The unit in control of speech, for example, will report that another “person” inside her is talking to her or giving her orders, these orders being experienced not from the standpoint of giving them but from an external standpoint, as coming from another person. This form of DID is called the coconscious form in the literature. Note that this term names something very different from what, for example, James or Parfit had in mind when they said that (what they call) coconsciousness is central to unified consciousness.

…

In the coconscious form, rotating amnesias usually play little or no role; they are central in the serial form. Indeed, the coconscious form resembles thought insertion (Billon and Kriegel, this volume), and even anarchic hands (Mylopoulos, this volume), more closely than it does serial DID.

Gennaro, R. J. (2015). Disturbed consciousness: New Essays on Psychopathology and Theories of Consciousness. MIT Press.

—64

THE CRUCIAL IMPORTANCE OF DUAL ATTENTION

To achieve these results, EMDR requires dual attention, or coconsciousness, between the personality part that is well-oriented to the safe present and the parts that hold the memory containing the posttraumatic disturbance. (Actually, this need for dual attention is necessary not only for therapy within the EMDR model but also within other models of treatment for trauma and dissociation.) Dual attention means that the person sitting in the therapist’s office is able to maintain a sense of orientation to the present, orientation to needed positive qualities of self, and awareness of the therapist’s liking, respect, and competence.

Knipe, Jim. EMDR Toolbox: Theory and Treatment of Complex PTSD and Dissociation. 2015

—65

Original

Metaphors of team members playing a favorite sport or different ingredients mixed together for a favorite dessert (symbolizing parts of the self blending together) are an effective and fun means to help dissociative children understand coconsciousness, erode amnesic barriers, and promote integration. This metaphor can be used throughout treatment to reinforce unity and eventually integration—one unified child playing hockey. This final symbolic picture could be drawn at the time of integration (Waters and Silberg, 1998b).Traducción

Las metáforas de los miembros del equipo que juegan un deporte favorito o diferentes ingredientes mezclados para un postre favorito (que simbolizan partes del yo que se mezclan) son un medio efectivo y divertido para ayudar a los niños disociativos a comprender la coconciencia, erosionar las barreras amnésicas y promover la integración. Esta metáfora se puede usar a lo largo del tratamiento para reforzar la unidad y eventualmente la integración: un niño unificado que juega al hockey. Este cuadro simbólico final podría dibujarse en el momento de la integración (Waters y Silberg, 1998b).

Wieland, Sandra, PhD. Dissociation in Traumatized Children and Adolescents. 2010

—66

Original

Do not talk too much about integration or fusion between parts, especially at the start. In many cases, parts are afraid that if this happens they will die. It works better to talk about walls between “inside people” no longer being needed than about the “people” disappearing or merging. Respect their choice not to fuse until and unless they are ready. My experience is that as parts share experiences and memories, the walls between them dissolve, either gradually (when they are coconscious much of the time) or suddenly (during a major piece of memory work), and the integration naturally happens when they are ready. Not all survivors will be capable of integration, and it can be dangerous to insist on it. It takes inordinate strength to tolerate awareness of all of a life of horrendous abuse.Traducción

No hable demasiado de integración o fusión entre partes, especialmente al principio. En muchos casos, las partes tienen miedo de que si esto sucede morirán. Funciona mejor hablar de muros entre «personas internas» que ya no son necesarios que de «personas» que desaparecen o se fusionan. Respete su elección de no fusionarse hasta que estén listos. Mi experiencia es que a medida que las partes comparten experiencias y recuerdos, los muros entre ellos se disuelven, ya sea gradualmente (cuando son coconscientes la mayor parte del tiempo) o repentinamente (durante un trabajo de memoria importante), y la integración ocurre naturalmente cuando están listos. . No todos los sobrevivientes serán capaces de integrarse y puede ser peligroso insistir en ello. Se necesita una fuerza desmesurada para tolerar la conciencia de toda una vida de horrendo abuso.

Hoffman, Wendy. Miller, Alison. From the Trenches: A Victim and Therapist Talk about Mind Control and Ritual Abuse. 2017

—67

Original

The first psychophysiological study of DID was done by the eminent neurologist-psychologist Morton Prince and a psychiatrist colleague (Prince & Peterson, 1908). The objective was not to study DID per se, but to determine if the psychogalvanic reaction (SCR) could be useful to corroborate the existence of coconscious (sometimes called subconscious) ideas. The DID patient was «made use of» as particularly suitable for this purpose. The patient had a «normal» identity and two alters, one of which claimed amnesia for both other identities. The identities could all be hypnotized, and only one of these hypnotic states was coconscious with the other hypnotic states as well as the unhypnotized identities. A number of studies were performed on this patient using electrodermal reactions to words that on the basis of bad dreams or past experiences had conscious emotional significance to some identities (and/or hypnotic states) and not to others.Traducción

El primer estudio psicofisiológico del TID fue realizado por el eminente neurólogo y psicólogo Morton Prince y un colega psiquiatra (Prince & Peterson, 1908). El objetivo no era estudiar el TID per se, sino determinar si la reacción psicogalvánica (SCR) podría ser útil para corroborar la existencia de ideas coconscientes (a veces denominadas subconscientes). El paciente TID fue «utilizado» como particularmente adecuado para este propósito. El paciente tenía una identidad «normal» y dos alters, uno de los cuales reclamaba amnesia para las otras dos identidades. Todas las identidades podían ser hipnotizadas, y solo uno de estos estados hipnóticos era coconsciente con los otros estados hipnóticos, así como con las identidades no hipnotizadas. Se realizaron varios estudios en este paciente utilizando reacciones electrodérmicas a palabras que, sobre la base de malos sueños o experiencias pasadas, tenían un significado emocional consciente para algunas identidades (y/o estados hipnóticos) y no para otras.

Larry K. Michelson. William J. Ray. Handbook of Dissociation: Theoretical, Empirical, and Clinical Perspectives. 1996

—68

Much as isomorphic MPD is puzzling because there is an apparent lack of alternating personalities, so coconscious MPD is confusing for its apparent lack of amnesia. Such cases present with apparent alters that know about one another and do not demonstrate time loss or memory gaps. Usually there is amnesia, but it is covered over or relates to events long past, and becomes apparent only in therapy.

Kluft, R. P. (1991). Clinical Presentations of Multiple Personality Disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 14(3), 605–629. doi:10.1016/s0193-953x(18)30291-0

—69

Original COCONSCIOUSNESS AND COPRESENCE

Coconsciousness is a term that has been used in the dissociation field since the 19th century, when dyspyschism was a major model of the mind (Ellenberger, 1970; R. P. Kluft, personal communication, April 1, 2013). The term refers to the degree to which parts are aware of each other internally. If the amnesia barriers are quite impermeable, there is little coconsciousness. If the amnesia barriers are thin and permeable, the parts may be said to be highly coconscious. A patient’s parts may vary in how much coconsciousness they have with some parts versus other parts (Kluft, 1984a).

–

In contrast, copresence, a term introduced by Kluft (1984b) to address important nuances not captured by the term coconsciousness, refers to the degree to which a patient’s parts can be forward in the body, executive, and aware of their presence in, for example, the therapist’s office at the same time. A part is said to be present when that part experiences itself seated in the chair in the therapy office, is observed by the therapist to be present at least in executive control of part of the body, and is using the first-person pronoun, “I.” Sometimes it happens that the therapist observes that one part seems to have control of the mouth, or mouth and head, but not the rest of the body.

Traducción COCONCIENCIA Y COPRESENCIA

Coconciencia es un término que se ha utilizado en el campo de la disociación desde el siglo XIX, cuando el dispsiquismo era un modelo importante de la mente (Ellenberger, 1970; R. P. Kluft, comunicación personal, 1 de abril de 2013). El término se refiere al grado en que las partes se conocen internamente. Si las barreras de amnesia son bastante impermeables, hay poca coconsciencia. Si las barreras de amnesia son delgadas y permeables, se puede decir que las partes son altamente coconscientes. Las partes de un paciente pueden variar en la cantidad de coconsciencia que tienen con algunas partes versus otras partes (Kluft, 1984a).

–

Por el contrario, la copresencia, un término introducido por Kluft (1984b) para abordar matices importantes no captados por el término coconciencia, se refiere al grado en que las partes de un paciente pueden estar adelantadas en el cuerpo, ejecutivas y conscientes de su presencia en, por ejemplo. ejemplo, la oficina del terapeuta al mismo tiempo. Se dice que una parte está presente cuando esa parte se siente sentada en la silla en la oficina de terapia, el terapeuta observa que está presente al menos en el control ejecutivo de una parte del cuerpo y está usando el pronombre en primera persona, “Yo.» A veces sucede que el terapeuta observa que una parte parece tener el control de la boca, o boca y cabeza, pero no el resto del cuerpo.

Ulrich F. Lanius PhD, Sandra L. Paulsen PhD, Frank M. Corrigan MD. Neurobiology and Treatment of Traumatic Dissociation: Towards an Embodied Self. 2014

—70

Original A dissociative child who is amnesic to his behavior may not be able to admit to his behavior unless he has coconsciousness and awareness of his alter’s offending behavior. My experience with dissociative children indicates that while behavioral interventions need to be in place, they have minimal impact on the child’s ability to control himself and learn from the consequences.

Traducción Un niño disociado que es amnésico a su comportamiento puede no ser capaz de admitir su comportamiento a menos que tenga coconsciencia y conocimiento del comportamiento ofensivo de su alter. Mi experiencia con niños disociativos indica que, si bien es necesario implementar intervenciones conductuales, éstas tienen un impacto mínimo en la capacidad del niño para controlarse a sí mismo y aprender de las consecuencias.

Joyanna L. Silberg. The Dissociative Child: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management. 1998

—71

Rather the coconscious personality reports the experiences of the other as something of which he becomes aware as experiences foreign to himself; he knows what the other thinks and feels, but he has also his own thoughts and feelings about the same object or topic.

In just such a way was Eve Black coconscious with Eve White and Jane with both Eves. eve White enjoyed no coconsciousness with either of the other two. Eve Black, it will be recalled, never gained access to Jane’s consciousness.

Thigpen, C. H., & Cleckley, H. M. (1957). The three faces of Eve. McGraw-Hill.

—72

In typical or true MPD (Figure 13), even knowledge is fragmented. All elements of BASK are encoded as elements of discrete personalities. Here we see the host personality A who has no coconsciousness, and D who has periods of both executive control and co-consciousness. Also present are Fragment C with co-consciousness, and Fragment B without co-consciousness. In the total system of available memories, the memories sum to more time than actually elapsed. The explanation for this is co-consciousness, and what one might call the «Rashomon phenomenon» where two personalities view an event from-different perspectives. Sometimes a multiple can be identified because of these incongruent memories.

Braun, B.G. (1988). The BASK model of dissociation.

—73

Before continuing, I wanted to make sure Rhonda was sufficiently coconscious to hear our conversation. So I asked, “Before we talk more, could I speak to Rhonda for a moment?”

He replied, “Yes. I can get her, but she can’t get to me.”

Sweezy, M., & Ziskind, E. L. (2016). Innovations and Elaborations in Internal Family Systems therapy. Routledge.

—74

The appearance of these alter personalities may be on a «coconscious» basis (ie, simultaneously coexistent with the primary personality and aware of its thoughts and feelings) or separate consciousness basis (ie, alternating presence of the primary and alter personalities with little or no awareness or concern for the feelings and thoughts of each other), or both.

Ludwig AM, Brandsma JM, Wilbur CB, Bendfeldt F, Jameson DH. The objective study of a multiple personality. Or, are four heads better than one? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972 Apr;26(4):298-310. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750220008002. PMID: 5013514.

—75

In this passage, the child alter personality, Elizabeth, who holds paternal-incest memories, is asking to come into therapy and disclose the trauma, and the adult host personality is coconscious and agreeing to the request. If this is correct, then the proper response would be to work actively with Elizabeth in therapy. How do the biographer and Dr Orne justify suppressing Elizabeth as a regressive role-play?

On page 57, the biographer devotes several paragraphs to doubting the reality of the sexual abuse, pointing out that Anne was reading about incest at the time she was making the disclosures, and adducing the family’s denial as evidence in favour of the memories not being real. What about Dr Orne?

Ross, Colin. The Osiris Complex: Case Studies in Multiple Personality Disorder. 1994

—76

Develop Coping Skills for All Available Parts

Besides information on developing skills taught in Chapter 4, people with DID benefit from being encouraged/taught to use their parts to manage life. For example, the parts who manage work may come home tired. They can rest in their safe spaces while other parts take over to make dinner. Or, if a part is triggered, another part can take over to help. Clients can also be encouraged to have more than one part out at once be coconscious, which for example, simplifies discussing plans. Parts working together inside, leads to more integrated functioning.

Joanne Twombly. Trauma and Dissociation Informed Internal Family Systems: How to Successfully Treat C-PTSD, and Dissociative Disorders. 2023

—77

What is the structural status of an alter personality late pre-integration? Prior to final fusion, the EP and host ANP are fully co-conscious, there are no intrusions or withdrawals, and everything has been processed and healed. All that remains is the integration ritual. At this stage the EP still has a subjective sense of self but there is no pathological dissociation going on.

After the fusion, the ANP mourns the loss of the EP and says, “She’s still with me in my heart.”

Ross M.D., Colin A.. Structural Dissociation: A Proposed Modification of the Theory. Manitou Communications, Inc. Edición de Kindle. 2013

—

(actualizando poco a poco)

Wow! No tengo palabras para definir la calidad de la información y lo documentado que está todo. Me animo a comentar porque no me puedo creer que nadie haya comentado antes. Me parece un concepto muy complejo, no lo acababa de entender, gracias por explicarlo.