Fusión y unificación de alters. Referencias

En el contexto de Trastornos Disociativos, hay términos para referirse a la dinámica de separación-unión entre partes disociadas de la identidad. Aquí explicamos brevemente y compartimos referencias para aclarar la confusión que pudiera darse. Y a veces se suelen usar indistintamente en un mismo texto.

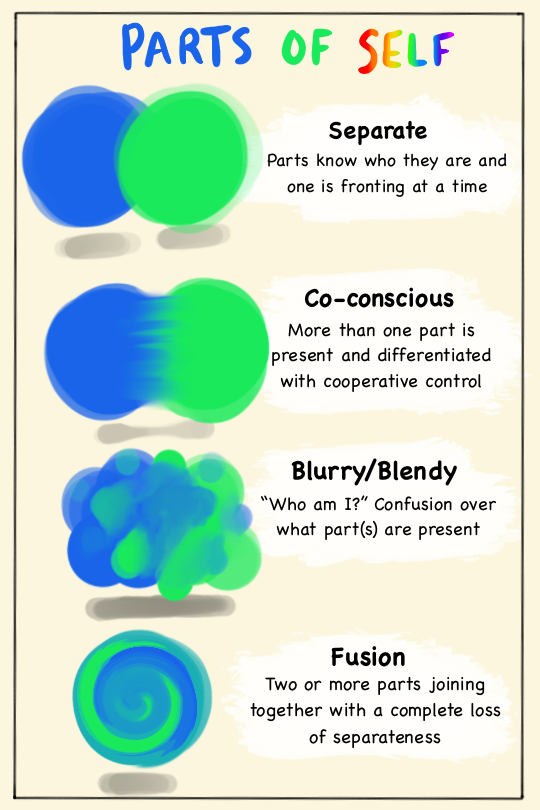

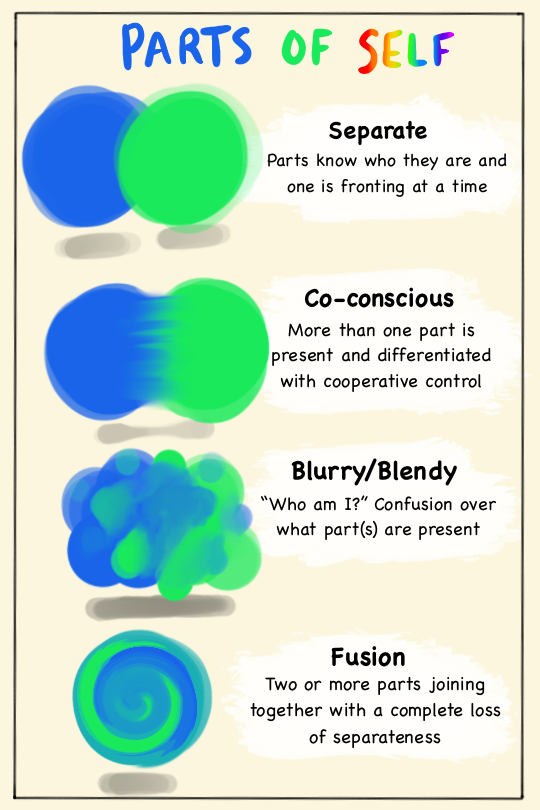

Arte de clever-and-unique-name.tumblr.com

Integración.

Este es el concepto más global y extendido. Puede significar:

- Lo opuesto a separar/disociar

- Un «proceso adaptativo que involucra acciones mentales y conductuales que ayudan a asimilar experiencias y sentido de sí mismo a lo largo del tiempo y los contextos».

- Identificación, cooperación y trabajo en equipo entre partes disociadas, sin fusión

- Un paso para la autocompasión

- Puede o no referirse a la fusión entre partes disociadas

- Integración de funciones entre partes. Por ejemplo, un alter no sabe escribir, pero integra el conocimiento de otros alters que sí. Siguen separados, pero esa barrera disociativa queda disuelta y ahora ese alter sabe escribir.

Co-consciencia

Es un concepto también amplio que abarcamos en su propio artículo. Puede significar:

- Cuando una parte es consciente de la otra

- Cuando dos partes son conscientes entre sí

- Cuando una parte que no está en control ejecutivo permanece consciente y atento

- También puede referirse al co-fronting

Co-fronting

Cuando dos partes están en control ejecutivo al mismo tiempo, sin mezclarse ni confundirse entre sí. Aunque la experiencia puede ser confusa y extraña.

Mezcla ó Combinación ó Blending

Cuando dos identidades o partes que continúan siendo entidades separadas se unen temporalmente hasta confundirse entre sí. Un paso previo a la fusión parcial.

Fusión Parcial

Fusión temporal. Puede ser breve, de unos momentos en terapia, puede hacerse en casa como práctica o puede suceder espontáneamente.

Fusión

«Un momento puntual en el tiempo cuando dos o más identidades alternantes tienen la experiencia de unirse con una pérdida completa de separación subjetiva.» Dos o más identidades que previamente estaban separadas se perciben ahora como una sola identidad más compleja con características de ambas.

Fusión Final/Total/Completa o Unificación

«Una total integración, unión y pérdida de separación— de todos los estados de la identidad.» Kluft menciona una fusión que no se desfusione durante 3 a 27 meses, se puede considerar una fusión permanente.

La permanencia y estabilidad de esta fusión sigue en debate.

No confundir esta fusión con conceptos como:

- Fusión (relaciones): acercamiento extremo entre dos personas que es poco saludable, y sucede cuando se pierden los límites y la individualidad, especialmente de una persona dependiente de la otra. Se confunden los pensamientos, deseos y emociones propias con las de la pareja o familiar.

- Fusión cognitiva: tendencia a creer el contenido literal del pensamiento y del sentimiento. La defusión sería dejar de identificarse en esas emociones y pensamientos y verlos desde una perspectiva. Similar a metaconsciencia. En la terapia cognitivo conductual, la fusión cognitiva es entre el «yo y los pensamientos», y para poder analizar los pensamientos hay que separar el yo de ellos. «No eres lo que piensas»

Referencias

Nota: resaltado y subrayado por la autora de este blog, no del texto original.

—1

Las Pautas para el tratamiento del trastorno de identidad disociativo en adultos de la ISSTD (2011) indican:

Existen determinadas cuestiones con las que todo terapeuta se va a encontrar durante el trabajo terapéutico con personas no integradas: la fusión, la combinación, la mezcla y la unificación. El resultado que se desea obtener del tratamiento es un tipo de integración funcional o una armonía entre las diferentes identidades que se van alternando. En ocasiones, términos como integración y fusión se utilizan de forma confusa. La integración es un proceso extenso y longitudinal relacionado con todo el trabajo realizado a lo largo del tratamiento sobre los procesos mentales disociados. La fusión se refiere a un momento puntual en el tiempo cuando dos o más identidades alternantes tienen la experiencia de unirse con una pérdida completa de separación subjetiva.

EL RESULTADO DE LA INTEGRACIÓN

Nuestro yo o nuestra personalidad no es el agente activo de integración, sino que más bien es el resultado de la integración (Loevinger, 1976; Metzinger, 2003; Van der Hart, Nijenhuis y Steele, 2006). A medida que los pacientes superan sus fobias es menos necesario dedicar tiempo a estar separados, y la fusión entre las partes puede ocurrir espontáneamente o con nuestra ayuda.

El resultado más estable del tratamiento es la fusión final —una total integración, unión y pérdida de separación— de todos los estados de la identidad. Sin embargo, incluso después de someterse a un tratamiento considerablemente largo, un número importante de pacientes con TID no son capaces de lograr la fusión final y/o no consideran que la fusión sea algo deseable.

—2

Como ya mencionamos, un paso intermedio puede ser la mezcla de dos o más estados de ego para lograr un determinado propósito, por ejemplo, para aprender a hacer algo que el otro sabe hacer, para darse mutuamente apoyo moral, o quizás para sentirse más fuerte con esta relación cuando están en algo nuevo, extraño o atemorizador.

Recuerde que la mezcla es temporal. Esto es lo que la hace relativamente segura. Normalmente, puede producirse en la consulta mediante hipnosis (ver Sección 5) y practicarse en la casa del paciente. Pasado un tiempo, la mayor parte de los pacientes logran hacerlo por sí solos, aunque usualmente prefieren comenzar una nueva mezcla en la consulta del terapeuta. Estas mezclas pueden durar un tiempo considerable, quizás varios meses. Algunas veces los estados de ego involucrados en la mezcla pueden decidir hacerla más permanente, en cuyo caso se convierte en una fusión. Pero una fusión no puede forzarse, ni desde dentro (por los propios estados de ego) o desde afuera (por el terapeuta).

A veces, la familia del paciente decide que la mezcla es preferible a los estados de ego individuales y trata de persuadir al paciente para que haga la fusión. Esto no funciona. El paciente puede sentirse presionado y hasta no respetado, y usualmente se niega.

Hunter, M. Manual médico para el personal cubano de la salud sobre trastornos disociativos.

—3

Primary Findings

Patients not reaching fusion showed little difference between pre- and post-MMPI profiles. 16.7% fused at median 39 mo FU. Those who reached fusion had means suggesting slight improvement on 2 scales at FU although samples too small for analyses. Overall, limited change noted.

Brand, B. L., Classen, C. C., McNary, S. W., & Zaveri, P. (2009). A Review of Dissociative Disorders Treatment Studies. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197(9), 646–654. doi:10.1097/nmd.0b013e3181b3afaa

—4

We thought if we ignored the multiple personalities, perhaps that would integrate them, but actually it’s just caused them to go underground. We’ve got to continue to stress the need for responsibility and accountability, but we’ve got to avoid repressing the various personalities.”

He pointed out that if there was to be any hope of achieving fusion so that Milligan could go to trial, all the personalities would have to be recognized and dealt with as individuals.

—5

Unification is considered a desirable goal by most workers in the field, although several therapists have expressed and explored the view that a negotiated settlement or reconciliation of the personalities, considered a stage in treatment by most, may be a more readily achievable and/or preferable end point or goal than unification. No controlled study has demonstrated the superiority of either outcome, but I have followed up patients who sought unification and those who declined to pursue it. I found that patients who achieved and retained unification fared better than those who did not. I noted that of the latter, in those patients who give priority to cooperative function, there is a spontaneous trend toward unification, while in those who give priority to the preservation of separateness, there was often decompensation in the face of intercurrent stressors, and the resurgence of conflicted clinically apparent MPD.

Currently, unified MPD patients are fast becoming a significant clinical subgroup, and will become increasingly common as more therapists develop experience and expertise with this condition. I distinguished among (1) unification, an overall term for the personalities blending into one, (2) fusion, the point in time at which the patient satisfies certain stringent criteria for the absence of residual MPD for three continuous months, and (3) integration, a more comprehensive process of undoing all aspects of dissociative dividedness that begins long before the first personalities come together and continues long after fusion until the last residua of dissociative defenses are more or less undone.512″15 To avoid terminologic complexities, the term unification will be used throughout this article unless the technical distinctions noted above are relevant.

…

It is humbling to reflect (somewhat whimsically) that the cure of multiple personality disorder leaves the patient afflicted with single personality disorder, the state in which most patients seek psychotherapy.

—6

Disclosures and requests for help by one part of the system, without the agreement of other parts, are likely to generate internal civil war. This may be particularly intense if there is an idea that the therapist would favour fusion of personalities or abolition of certain troublesome personalities. This would be equivalent to an external agency taking sides in a conflict within a country.

One point that cannot be emphasised too highly is that for many patients a multiple personality system has been established as a means of surviving. To threaten this system may be experienced as a threat of death. In this way the therapist may be perceived as utterly dangerous, either through malevolence or ignorance. Nevertheless, the fact that the patient is presenting for treatment at all means that in some respects the system created for defence is breaking down, and this creates the motive for therapy.

My own stance is to tell the patient explicitly that the model I work with is one that aims to facilitate the development of internal communication and democracy. I explicitly use this political metaphor, emphasising that it is not my role to impose a solution, or to take sides.

—7

The question of integration

When therapists began working with dissociative persons, the explicit goal was generally integration or fusion, a term that was used to mean fusing all the insiders into one person. This was usually conducted through a ceremony that joined the entire system or major parts, and was artificially induced by therapist-directed hypnosis. It often did not work, or created more problems than it solved.

My experience after twenty years of working with dissociative people, including those with mind control and ritual abuse histories, is that parts often naturally join with one another when there is no longer a need for them to remain separate, to protect secrets, or to keep toxic emotions or body sensations from flooding the whole person. There is no need for you to deliberately make it happen, unless there is a special reason to hurry.

…

Steven Frankel: “Learning to blend”

I teach blending as a skill. I want my patients to learn how to do it and undo it, so they have control over whether/when/for what purpose(s) to do it. It happens to be a skill that provides experiential learning of what fusion feels like, so they will have a referent for that experience and not be so afraid that fusion means that some will die or disappear (the most common concerns about fusion). Blending also gives them an experiential lesson in the difference between being “not alone” («blended”) vs. alone (unblended).

…

Integration is more of a journey than a specific goal, and it doesn’t have to mean total fusion. During the course of my recovery, I found that the “walls” between my different parts grew thinner. At first, my parts became aware of one another’s presence. Then it got easier to communicate with each other and to work together to build a community. More parts were able to participate in my daily life and to feel that they mattered. It also became easier to find and rescue parts that were still in unpleasant situations inside.

—8

Trastorno de identidad disociativo

El objetivo del tratamiento es el funcionamiento integrado.

La identidad que tiene el control, por lo general, habla en primera persona y puede conocer algunas de las otras partes o desconocerlas por completo El núcleo del proceso terapéutico es ayudar a las identidades a reconocerse mutuamente como partes legítimas del yo y a negociar y resolver sus conflictos.

El resultado del tratamiento más deseable es la fusión final de todos los estados de identidad. Sin embargo, incluso después de someterse a un tratamiento prolongado, un número considerable de pacientes con TID no podrá lograrla. Un resultado más realista a largo plazo para algunos pacientes puede ser un acuerdo cooperativo entre las identidades alternativas para promover un funcionamiento óptimo.

—9

The concept of “fusion,” maintained as a major goal of treatment by most investigators, becomes problematic when we consider that we are always multiple at the ego state level. I prefer the term integration, which doesn’t imply a melting into one great big “Oneness” which many alters would fight with the full force of the survival instinct. Whether or not the difference is only semantic, to aim for peaceful coexistence under a coherent executive, feels like a more modest goal to patient and therapist alike, and when successful leads to behavior indistinguishable from the “fused” patients so often reported. Former alters remain present but do not “come out,” or when they do it is more like when any person shifts ego states; continuity of selfhood proper is restored.

John O. Beahrs M.D. (1983) Co-Consciousness: A Common Denominator in Hypnosis, Multiple Personality, and Normalcy, American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 26:2,100-113, DOI: 10.1080/00029157.1983.10404150

—10

Integration is much more than eventual “fusion” of dissociative parts of the individual into a more cohesive and coherent personality. An integrated personality includes a unified sense of self (e.g., Kluft & Fine, 1993; Ross, 2001), as well as ongoing integrative actions that support functioning in everyday life, including regulatory and reflective skills. Integration is an adaptive process involving mental and behavioral actions that help to assimilate experiences and sense of self over time and contexts. Well-integrated individuals have a consistent sense of who they are, realizing they can grow and change, while remaining the same person. Such a person experiences him- or herself as “me,” regardless of what he or she is thinking, feeling, or doing, and remains grounded in the present when remembering traumatizing events, and experiences the recall as an autobiographical narrative memory rather than a reliving of the past. Moreover, the person typically is able to recognize and accept reality for what it is, including his or her history and present circumstances, acting adaptively based on present circumstances rather than reacting with habituated dysfunctional patterns.

Courtois, C. A., Norton-Ford, J. D., Herman, J. L., & Van Der Kolk, B. A. (2009). Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based guide. In The Guilford Press eBooks.

—11

Continuing Discourse No. 1: … But not Sufficient for Health. Although the texts promote integration as being the cure for dissociative identity, they then state that more is needed to achieve health; that is, integration is necessary but not sufficient for health: “Treatment does not end with fusion/integration; it only enters a new phase” (Putnam, 1989, p. 302). There is also the tacit message that on this path to “true health” the “patient” will develop further psychological problems: “The initial euphoria that accompanies the achievement of unity rapidly gives way to a profound depression” (Putnam, 1989, p. 318). “When you complete the multiple personality part of the treatment and the person has achieved integration, you are then dealing with a person with single personality disorder” (Kluft, 1993, p. 89; 1994)

Clayton, Kymbra. (2005). Critiquing the Requirement of Oneness over Multiplicity: An Examination of Dissociative Identity (Disorder) in Five Clinical Texts. E-Journal of Applied Psychology. 1. 10.7790/ejap.v1i2.21.

—12

We have come to the point where many of us have joined or inte- grated into others and before the end of this life, more will blend to make fewer. We doubt seriously, however, that we will ever fuse to make “one.”

We don’t consider this such a bad future.

Many people think that multiples must be «one» before they are considered cured. This may be the case for many multiples, and we consider them fortunate. But other multiples, like us, will be grateful for a compromise among our selves. We want people to understand that we may never be considered an individual. We want people’s love and respect anyway.…

A person can be “healthy” without having to integrate all of his or her parts. Integration should be an option, but not the only option, in one’s pursuit of mental health and a good life. —IR.T

Cohen, B. M., Giller, E., & Lynn, W. (1991). Multiple personality disorder from the inside out.

—13

It should be noted that structural dissociation is a chronic condition that exists until fusion among all parts occurs. This means that there is not one part of the personality that is dissociated and another that is not. Similarly, there are not times when an individual is dissociated and times when he or she is not. In

Paul F. Dell. (2009) Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders (p. 301). Taylor and Francis. Kindle Edition.

—14

It is important for each new part also to get a new job. This provides respect for those parts of the self that dissociated when life was overwhelming and the “overwhelm” could not be absorbed within the functioning self. Receiving a new job and a new name also enables the young child to embrace and accommodate this part of the self, thus promoting integration and establishing an integrated sense of the self. Waters and Silberg (1996: 168) stated, “The authors believe that the fusion and eventual integration of all of the dissociative child’s split-off parts is crucial to assisting the child to learn in school, to engage in appropriate behaviors, to develop his/her capabilities, and to form meaningful and lasting relationships. As long as fragmentation exists, the dissociative patient relies more on his or her dissociative defences, and this coping style becomes increasingly more ingrained.”

Wieland, S. (2011). Dissociation in traumatized children and adolescents.

—15

The final approach in Fraser’s article addresses the issue of fusion or integration, a strong area of potential controversy for those diagnosed with or identifying as DID. Many individuals with DID strongly resist or oppose a psychiatrist or any other provider’s insistence that they integrate the various aspects of their personality into a cohesive whole. This process can feel disrespectful to the members of a system, and if you are reading this passage and have ever felt triggered at the suggestion that you need to integrate, you are not alone. In the following section where contributors speak to how their systems operate, you will read many insights around whether the word and concept of integration works (for two of our contributors it does), or whether other ways of looking at healing (e.g., cohesion, unity, community, diplomacy) are a better fit.

Marich, J. Pollack, J. (2023) Dissociation Made Simple: A Stigma-Free Guide to Embracing Your Dissociative Mind and Navigating Daily Life

—16

During the interviews different identities and personality fragments took full control spontaneously and they had various degrees of amnesia for one another’s activities and different degrees of knowledge about one another. These identities also executed many aspects of the patient ‘ s life for which host was amnesic (e.g., extramarital relations, travelling to several places). This patient reached fusion after two years of psychotherapy including inpatient treatment of six months of total duration spread over these admissions. Postfusion treatment of the patient is under progress.

H, Tutkun & Yargic, Ilhan & Sar, Vedat. (1996). Dissociative Identity Disorder Presenting as Hysterical Psychosis. Dissociation. 9. 241-249.

—17

There may be times when an ego state may wish to let the others know of an event or events that should be known by the others before any attempt at fusion (joining together). It usually is better to do experience sharing in bits and pieces rather than have the floodgates open by a fusion without any preparation. It is the nature of dissociation that traumatic or frightening events may be in the memory bank of some but not all ego states. With fusion, these amnestic barriers generally break down. It is best not to have to deal with new traumatic material at unplanned moments.

Fraser, G. A. (2003). Fraser’s “Dissociative Table Technique” Revisited, Revised: A Strategy for Working with Ego States in Dissociative Disorders and Ego-State Therapy. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 4(4), 5–28. doi:10.1300/j229v04n04_02

—18

Fomentar la fusión

En última instancia, la superación de la fobia a las partes disociativas debe incluir la fusión, “el acto o el caso de juntar dos o más [partes de la personalidad] personalidades o fragmentos con objeto de combinar su esencia en una única entidad” (Braun, 1986, p. xv; cf., Kluft, 1993c). Las víctimas traumatizadas suelen temer y evitar la fusión. Esta aversión se puede entender como una subtipo específico de fobia a las partes disociativas. Para que el paciente pueda superar esta fobia, el terapeuta debe analizar decididamente las resistencias a la fusión, y no insistir en que las partes se fusionen antes de que el nivel mental del paciente pueda tolerarlo.

Las acciones integradoras que derivan en la fusión de dos o más partes disociativas son propias de la labor de la fase 3 (véase el capítulo 17). Ahora bien, tales fusiones parciales de la personalidad pueden acontecer antes dentro del tratamiento, a la manera de una breve incursión en la fase 3.

Van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E. R. S., Steele, K., van der Hart, O., & Ruiz, F. C. (2011). El yo atormentado: La disociación estructural y el tratamiento de la traumatización crónica. Desclée De Brouwer.

—19

After trauma processing, spontaneous integration may take place. If the spontaneous integration of a dissociative state has not taken place, it will be necessary to help the child with this by specifically focusing on integrating this dissociative state. Through internal communication the child can change the name and the function of the dissociative state to adapt to a more acceptable role. Integration can also be explained with metaphors like a soccer team. The team can only win when all parts of the team work together. Activities supporting the process of integration are: visual experiences (i.e. the painting of a rainbow in which several colors flow together) or tactile experiences (i.e. taking different colors of clay and building a ball out of it) whereby each color symbolizes a single part, fusion rituals or figures in the sand tray symbolizing the different dissociative states come closer, hold hands (Waters, 1998). Waters (2016) describes symbolic drawings of integration as well as the use of EMDR during the integration of dissociative states.

Agarwal V, Sitholey P, Srivastava C. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of Dissociative disorders in children and adolescents. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019 Jan;61(Suppl 2):247-253. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_493_18. PMID: 30745700; PMCID: PMC6345132.

—20

After appropriate exploration and stabilization, fears of integration or fusion, or loss of identity or “death” may be addressed as negative cognitions and reprocessed accordingly. However, many EMDR clinicians report that spontaneous integration and fusion also occur.

…

Middle Treatment Phases

Throughout the Integration Phase of treatment, the therapist may find various uses for EMDR, including, for example, (1) EMDR’s prototypical application, the reprocessing of traumatic memory; (2) facilitation of internal dialogue using ego state therapy (Watkins & Watkins, 1997) during EMDR; (3) restructuring of cognitive distortions used as EMDR targets; (4) building of alternative coping behaviors using EMDR installations; (5) ego strengthening through installations; and (6) fusion.

Shapiro, F. (2017). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, third edition : Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures. The Guilford Press; Third edition

—21

The Flash technique can be used for several parts at the same time leading to the complete desensitization of trauma memories and the planned fusion of parts. Strengthening of resources with playful imagination and olfactory stimulation appeared to “boost” the session with increased positive feelings in the body and a faster processing time. Initially the aim was to use Flash therapy and then EMDR, once the memory intensity was tolerable for the parts. However, I found that in many sessions, EMDR did not need to be used at all.

Shebini N. Flash technique for safe desensitization of memories and fusion of parts in DID: Modifications and Resourcing Strategies. Front Psychother Trauma Dissociation. 2019;3(2):151–64.

—22

Help them “talk inside.” Although talking internally may seem to make the person “more” multiple, in that they will hear voices and become aware of more parts, it will actually improve communication between the front person and the other parts, and the long-term result will be that they will become better organized and work more like an integrated person. The goal is “co-consciousness,” with whichever part is “out” in the body being aware of the needs and viewpoints of all the other parts, so that effective decisions can be made by the whole person rather than by just one part at a time.

Do not talk too much about integration or fusion between parts, especially at the start. In many cases, parts are afraid that if this happens they will die. It works better to talk about walls between “inside people” no longer being needed than about the “people” disappearing or merging. Respect their choice not to fuse until and unless they are ready. My experience is that as parts share experiences and memories, the walls between them dissolve, either gradually (when they are coconscious much of the time) or suddenly (during a major piece of memory work), and the integration naturally happens when they are ready. Not all survivors will be capable of integration, and it can be dangerous to insist on it. It takes inordinate strength to tolerate awareness of all of a life of horrendous abuse.

Miller, A., Hoffman, W. (2017) From the Trenches: A Victim and Therapist Talk about Mind Control and Ritual Abuse, 1st Edition. Routledge

—23

Terms such as integration and fusion are sometimes used in a confusing way. Integration is a broad, longitudinal process referring to all work on dissociated mental processes throughout treatment. R. P. Kluft (1993a) defined integration as an

«ongoing process of undoing all aspects of dissociative dividedness that begins long before there is any reduction in the number or distinctness of the identities, persists through their fusion, and continues at a deeper level even after the identities have blended into one. It denotes an ongoing process in the tradition of psychoanalytic perspectives on structural change.» (p. 109)

Fusion refers to a point in time when two or more alternate identities experience themselves as joining together with a complete loss of subjective separateness. Final fusion refers to the point in time when the patient’s sense of self shifts from that of having multiple identities to that of being a unified self. Some members of the 2010 Guidelines Task Force have advocated for the use of the term unification to avoid the confusion of early fusions and final fusion.

International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation (2011): Guidelines for Treating Dissociative Identity Disorder in Adults, Third Revision, Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 12:2, 115-187

—24

Integration and Fusion

From our point of view, integration and fusion are not synonymous. Fusion suggests an amalgamation of all states into a single unit. Since we believe that the typical human being is not so fused, our goal is not fusion. Integration implies cooperation in a mutually needs-meeting resolution of differences. Sometimes two or more ego states find that their needs and the expression of those needs are so similar that it is no longer necessary or advantageous to divide their energies and be separate. They may simply decide to stay together. But that is their choice, not the therapist’s.

We have been asked whether activating ego states doesn’t increase dissociation. Paradoxically, ego state therapy does not increase dissociation. It decreases it. If an ego state is split off during trauma in childhood, that entity retains the feelings of the experience and the thinking of that moment in time. It does not grow up with the rest of the personality. It is as if that ego state were encased in a cocoon in which time had frozen and stood still. Communication and interaction between ego states increases boundary permeability and growth, resulting in reduced dissociation.

Michelson, L. K., & Ray, W. J. (Eds.). (1996). Handbook of dissociation: Theoretical, empirical, and clinical perspectives. Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0310-5

—25

The terms “dissociation” and “integration” have long been synonymous with one another—meant to signify that the only reasonable goal in working with splitting and compartmentalization must be the fusing together of dissociated parts to create one single “homogenized” adult. Daniel Siegel, however, makes a strong case against defining integration as fusion. He asserts (2010a) a different view: “Integration requires differentiation and linkage.” Before we can integrate two phenomena, we have to differentiate them and “own” them as separate entities. We can’t simply “act as if” they are connected without noticing their separateness. But, having clearly differentiated them so they can be studied and befriended, we then have to link them together in a way that fosters a transformed sense of the client’s experience, facilitating healing and reconnection.

…

Using Siegel’s definition of integration, fusion is not necessary nor is it as empowering as coherence, collaboration, and overcoming self-alienation. In this chapter, we will focus on how to foster integration by differentiating parts previously denied, ignored, or disowned, connecting to them emotionally, and providing experiences that replace self-alienation and self-rejection with self-compassion and secure internal attachment relationships.

—26

Although the aim of the treatment was articulated by the therapist during the preparation for the table technique, it is helpful to again state that all of the ego states are part of the system and that the aim of the treatment is the elimination of the dissociative barriers and the facilitation of harmony and cooperation. The assumption is that self-states are listening and many are suspicious. Movies and many therapists have suggested that the aim of this type of treatment is the fusion of ego states into one cohesive state. One should assume that a realistic paranoia exists internally and should continually, throughout the treatment, remind the adult self (or any other self that is active) that ego states are not eliminated or “killed,” not even the most virulent and angry ones. Anger and hate should be explained to contain the energy and assertiveness that was channeled into defense. Borrowing from systems theory, the context and function of these self-states needs to be explained as having been adaptive at one time.

—27

Ahora, esta fusión había ido aún más allá. Aquellos guardianes del pasado no integrado, con sus recuerdos airados y temerosos, habían regresado a Sybil. Tras hacer el retrato que Ramón había mirado, la última obra producida por ella, Peggy había dejado de existir como ente separado. Pero su fortaleza de carácter era muy notoria en la nueva Sybil.

—28

Although I think that fusion is a goal to be sought in cases of multiple personality, I do not believe that this is feasible in ali cases.

In the first place, sorne personalities are recalcitrant and refuse to cooperate in the fusion process. Pedro emphasized to me on several occasions that he would not permit himself to be weakened and that if he perceived that was happening in any sense, he would make sure the patient never returned to therapy. In the second place, and more importantly, Pedro was not a threat to Migdalia. On the contrary, Pedro had become something like «a guardian angel» to the extent that his goal was clear: he existed to help Migdalia and to provide her with enough strength to get through her moments of weakness.…

Achieving resolution-integration

Once the personalities have shared their secrets, their desires and fears, they are usually more open to the possibility of an eventual fusion. The main obstacle to this is that sorne personalities resist the process because they are afraid of «dying». The therapist has to explain to them that the process of fusion does not imply death per se, but rather the simultaneous re-integration of different functions that, before fusion, only appeared to be independent but were not actually separate.

Martínez-Taboas, A. (1995). Multiple personality: An Hispanic perspective. Puente Publications.

—29

Fusion: This sometimes occurs spontaneously but usually happens after extensive therapy. It is the moment in time during which two or more alters are divested of their separateness (Kluft 1993; Putman 1989). In clinical terms, it usually involves the coming together of two or more alters into a richer and fuller alter. It is usually the goal of therapy to fuse all of the alters into a coherent and nuanced personality who may have a range of emotions, but whose emotions are not experienced in separate alters. In reality little is known about the process of fusion, and what is known is derived from clinical and phenomenological observation. Furthermore, fusion may be at times only temporary, and two previously fused alters may especially in times of stress-become redifferentiated. In the case of GJ, after two years of therapy, her alters became less and less distinct.

David M. McDowell, Frances R. Levin & Edward V. Nunes (1999) Dissociative Identity Disorder and Substance Abuse: The Forgotten Relationship, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 31:1, 71-83, DOI: 10.1080/02791072.1999.10471728

—30

Integration, or the fusion of all alters into one personality, is a controversial topic. It is often a lengthy and subtle process, but a few studies have begun to show that treatment works and leads to stable integration (e.g., Coons & Bowman, 2001). Integration is associated with a wide variety of benefits, including reduction of non-dissociative symptoms (Coons & Bowman, 2001; Kluft, 1993b). Still, there are disagreements about its necessity, with some arguing that it is merely a by-product of therapy rather than its explicit goal (Fine, 1996).

—31

Fusion refers to the merger of two or more alternate personalities, resulting in the patient’s perception of their joining together, completely surrendering a sense of subjective separateness. Thus, progressive integration is the goal of therapy throughout the treatment process, whereas fusion occurs in the latter stages of treatment, usually in the middle and late phases.

Many experts in the treatment of DID advocate complete fusion as the most stable treatment outcome (e.g., Kluft, 1993), resulting in a full merger of all personality states. Early in treatment, most patients with DID have a strong investment in the separateness of the alternate personalities, seeing them as separate and autonomous entities. They have difficulty in perceiving any value in merging the identities, seeing this as destructive or annihilating rather than a joining of forces. As the treatment proceeds and individual characteristics and jobs or functions of the personalities become less differentiated, patients often become more amenable to some type of unification. However, such complete merger or fusion may not be possible for all patients with DID for a variety of reasons, including ongoing situational stress, extensive comorbidity of other psychiatric difficulties, or continuing narcissistic investment in the alternate identities. The ultimate pragmatic solution is a maximal level of cooperative and integrated functioning, even if complete fusion is not possible for a given patient.…

Failure to adequately pace treatment is also seen in premature attempts at integration and fusion. All too often, therapists and patients try to shortcut the treatment process by attempting fusion of personalities before adequate working through the underlying conflicts and traumatic events that led to their dissociation. Such misguided efforts have sometimes entailed strenuous efforts by therapists in the form of prolonged sessions and special techniques. These fusions usually either quickly disintegrate, or new personalities emerge to take on the functions of those who had been merged.

—32

Perhaps it would be better to make a distinction between fusion and integration. It is possible for alters to fuse into one, but just as in corporate mergers, there needs to be a lot of processing of «cultural differences.» While memories, skills, and knowledge can easily be pooled, differing values do not easily coexist. For nonmultiples, dealing with internal conflict is part of life. We have mixed feelings about many things. Much of the work of psychotherapy has to do with working out unconscious conflicts of values. When DID patients deal with conflict, it is experienced as a conflict between alters. The jockeying that goes on among alters is, in effect, the equivalent of singletons’ struggle with internal conflicts. As DID patients approach integration, they are shocked to find themselves inheritors of internal conflict. They are often taken by surprise since they have little experience in dealing with such conflict.

—33

One might easily see or read into the character Jane some fusion of, or even a mere compromise between, the diverse tendencies, of the two Eves. On her first appearance this expectation naturally arose. But it immediately became difficult for us to fit or even to force her-into such a concept.

—34

Putnam makes quite clear that, “Whatever an alter personality is, it is not a separate person” (p. 103). However, he goes on to say:

I have seen a number of therapists struggling implicitly or explicitly with the question, “Who is the patient?” while working with their first MPD cases. In such an instance, the “patient” in the therapist’s mind is originally the host personality, who presents for treatment. . . . The therapist must come to recognize that the patient really is a multiple and that the therapeutic work involves the whole personality system. (p. 109)

Putnam’s view of treatment derives from his understanding of the developmental basis of the disorder. In a more recent book (1997) he has said:

[T]he identity fragmentation seen in MPD and other disorders associated with childhood trauma is not a “shattering” of a previously intact identity, but rather a developmental failure of consolidation and integration of discrete states of consciousness. In particular, it is a profound developmental failure to coherently bind together the state dependent aspects of self experienced by all young children. (p. 126)

Elsewhere, in a case discussion (1992), he has elaborated:

We are not born into the world with a single, unified personality. . . [W]e may view [the patient] as someone who has failed to complete the developmental work of integrating a more-or-less continuous sense of self. (p. 101)

According to this perspective, in the treatment of Sandy, all the “alters” were my patient(s). It followed that I would need to have a relationship with all of them, to the degree possible, and treat them as equals within the system. “They” would ultimately determine whether or to what extent integration would occur, not the therapist and the “host” personality. Putnam warns (1989), “Before a therapist performs a partial or final fusion, the therapist should try to determine whether the alters are ready for such a fusion” (p. 306).

—35

Planned Fusion and Integration

There are many views of integration among both therapists and clients. Ultimately, it is the client who must decide which option to choose. The most commonly accepted approach centers on the belief that individual parts must fuse together to become one. Some therapists use very concrete methods for facilitating this process.

…

Spontaneous Fusion and IntegrationAnother belief about integration is that the final merging of parts occurs spontaneously, which is related to the earlier comment that integration is a process that is occurring throughout therapy. This approach takes the stance that a final goal of integration is not really the issue. Instead, integration of memory leads to increased awareness among parts. As parts continue to grow in awareness and operate more consciously, fusions among parts gradually begin to take place.

…

When a client is able to operate as a unified Self, either through fusion of parts or internal cooperation, for a distinct period of time, with continuous memory throughout that time, it is generally appropriate to move into postintegration therapy. Again, the stages of therapy are fluid and are delineated here to provide a treatment framework for the therapist.

Haddock, D. B. (2001). The Dissociative Identity Disorder Sourcebook. McGraw Hill; 1st edition

—36

In my own case, I experienced an even more bizarre transformation. Before my sleeping personality, Henry, finally emerged, I had approximately 20/30 vision, and Dana was forced to wear the standard over-forty corrective lenses. After the fusion of my personalities, I went to have my eyes reexamined and discovered that I suddenly had the vision of a twenty-year-old. I threw my glasses away and haven’t needed them since.

Hawksworth, H., & Schwarz, T. (1977). The Five of Me: The Autobiography of a Multiple Personality. Regnery Publishing.

—37

The Alliance, the first fusion within the Flock, occurred that night over tacos and beer. Neither Lynn nor I was exactly sure how this fusion would work, how tightly woven the three personalities would become.

Kendra, Isis, and I retained the individual right to pull out if we liked. I didn’t feel much change that night, but there were no longer any barriers to communication among the three of us.

The next day, the change was more apparent to me. Suddenly the world was filled with color, form, and design that I had missed through my neurotic focus on people alone. Isis and-I-together sees so much that I never saw as Renee-alone,” I told Lynn. “And there’s something else. I feel more like my own person now. Kendra has given me a protective coating. I don’t feel dependent on anyone’s acceptance, not even on yours.”

Lynn smiled lovingly. “The Flock is growing up.”

Casey, J. F., & Wilson, L. I. (1991). The Flock: the autobiography of a multiple personality. Ballantine Books

—38

Before describing these personalities, we should mention the circumstances presumably responsible for their liberating themselves from the prior merger or fusion. According to one of the personalities (Sammy), Jonah, suspecting that a new girl friend was cheating on him, came to her apartment one evening after a man had left it and found her naked. Jonah became extremely upset, and a physical altercation started. At that point, all the personalities apparently «defused» and one of them started beating up this girl. Since that time, the alter personalities have maintained separate existences with Jonah being amnesic for their behavior during their emergence.

Ludwig AM, Brandsma JM, Wilbur CB, Bendfeldt F, Jameson DH. The objective study of a multiple personality. Or, are four heads better than one? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972 Apr;26(4):298-310. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750220008002. PMID: 5013514.

—39

Case 19. A woman of 42 had over 1,600 separate entities. Virtually all were very minor entities, flickering briefly into action to influence the beleaguered host from behind the scenes. There was one additional very well articulated alter that never emerged unless requested to in the course of therapy. This patient exemplifies what Braun described as polyfragmented MPD. She did not appear to demonstrate classic MPD until she had unified down to three alters.

…

Extremely complex MPD patients frequently rush toward fusion prematurely, either to please the therapist or to evade dealing with painful issues in the treatment (often either strong feelings in the transference or the anticipated pain of the memories of other alters). Such apparent fusions fail nearly universally, and must be interpreted as indications for more work to be done rather than as proofs of a poor prognosis.

Kluft, R. P. (1988). The phenomenology and treatment of extremely complex multiple personality disorder. Dissociation: Progress in the Dissociative Disorders, 1(4), 47–58.

—40

What is the structural status of an alter personality late pre-integration? Prior to fi nal fusion, the EP and host ANP are fully co-conscious, there are no intrusions or withdrawals, and everything has been processed and healed. All that remains is the integration ritual. At this stage the EP still has a subjective sense of self but there is no pathological dissociation going on.

After the fusion, the ANP mourns the loss of the EP and says, “She’s still with me in my heart.”

Ross M.D., Colin A.. Structural Dissociation: A Proposed Modification of the Theory. Manitou Communications, Inc.. Edición de Kindle.

—41

Studies have shown that this kind of specialized treatment for people who have a dissociative disorder, when combined with medication for such symptoms as mood swings, depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive behavior, is highly effective. Richard P. Kluft, M.D., reported that 81 percent of 184 DID patients he treated achieved “stable fusion,” meaning that all signs of DID and related symptoms were absent for at least twenty-seven months. Regular follow-up visits for as long as two to ten years after treatment ended showed that these patients maintained a complete absence of clinical signs of a dissociative disorder. For a large subgroup of these patients who were high-functioning before they were diagnosed with DID, their treatment averaged two and a half years of a minimum of two forty-five-to fifty-minute sessions a week. Most patients who achieved integration discontinued treatment and remained essentially well during the follow-up period. Recent research indicates that length of treatment varies, three to five years being the average.

Steinberg, M., MD, & Schnall, M. (2010). The Stranger in the Mirror: The Hidden Epidemic. Harper Collins.

—42

The will of dissociative parts becomes more differentiated the more they contact, accept, and learn to cooperate with each other. This development reaches its summit when they eventually fuse, that is, become completely united. A fusion between formerly dissociated parts implies a coupling of the different will systems that were previously distributed over the involved dissociative parts. In this phase the patient learns to deal with polyvalences or inner conflicts that characterize common life and that pertain to contradictions among different wills, now under the umbrella of being one ‘I.’

…

The mental and phenomenal overlap among the dissociative parts increases during successful treatment; the mental and phenomenal differences eventually disappear altogether: They fuse. The fusion of dissociative parts thus implies the generation of new conceptions of self, world, and selfof- the-world. The new PCS and PCIRs partially include formerly dissociated experiences and conceptions (e.g., particular memories), but exclude others (e.g., the conceptions of being a child, of living in 1980 or thereabout, of living with deceased parents, of being caught in an eternally traumatizing life).

—43

La personalidad “host” (anfitriona) generalmente está deprimida, puede sufrir de TEPT y crisis disociativas agudas de las que puede permanecer amnésica. La fusión siempre debe de conducirse en presencia de o hacia la personalidad “anfitriona” porque la dirección de la fusión puede conducir a diferentes resultados. No se recomienda conducir una fusión entre personalidades alternas.

Sar, V., & Ozturk, E. (2012). Trastorno de Identidad Disociativo: Diagnóstico, Comorbilidad, Diagnóstico Diferencial y Tratamiento. Revista Iberoamericana De Psicotraumatología Y Disociación, 3(2).

—44

Existe un importante debate entre estas tendencias, pero los pacientes, que acostumbran siempre a ponernos en nuestro sitio, serán probablemente los que marquen el tipo de trabajo posible. Una de nuestras pacientes, que podríamos denominar de «alto funcionamiento», experimentó una fusión espontánea de sus partes disociadas después de cierto tiempo de trabajo con ellas. Otros pudieron hacerlo con más ayuda. En algunos casos los pacientes prefirieron no llegar a fusionarse con sus estados disociados, pero alcanzaron lo que podría denominarse una «convivencia pacífica». En los pacientes más graves el trabajo con las partes fue casi imposible, pero se ha podido mejorar parte de sus conductas disfuncionales. Por supuesto, ha habido casos que no han mejorado en absoluto (aunque, contra la idea que solemos tener sobre estos cuadros, no han sido la inmensa mayoría).

—45

As modern investigators have discovered, however, abreaction alone often does not undo the fractionation of the personality into isolated alters. Accordingly, once the alters have been recalled to consciousness and abreacted, their fusion and ultimate integration into a unified and stable personal identity can be accomplished only by breaking down the amnestic barriers between the individual alters using active therapeutic maneuvers that appear to rely heavily on hypnotic suggestion and the systematic desensitization of anxiety.

…

Overcoming the phobia of ordinary life.

Traumatic memories obstruct fusions between identities concerned, and a successful treatment of traumatic memories frees the way for it. With each fusion, another milestone toward integration of the personality is reached. Often, the fusion that patient and therapist regard as the last one (i.e., when unification has taken place) is not. Only when the dissociative symptoms have not reappeared after more than 2 years, Kluft (1987) states, may this fusion indeed be regarded as the final one. Integration is fostered first by stimulating identities to collaborate and negotiate with each other (the preparation phase).

When identities have learned to know each other, have shared their respective life histories and experiences, and have resolved their mutual conflicts and problems, then they are more clearly on the way to personal unity. The most frank way in which this happens is the fusion of two or more identities who are ready for it. There are DID patients who, even when all traumatic experiences seem to be integrated, continue living with a certain number of identities instead of aiming for unification. In our limited clinical practice, however, it appears that this decision always implies the existence of some other traumatic memories with which the patient tried to avoid dealing.

—46

Unification

The integration of all parts into a cohesive whole is called unification (Kluft, 1986b, 1993b). This usually occurs toward the latter part of therapy, at some point in Phase 3, though not always. A few patients may become nearly unified prior to the treatment of traumatic memory. In these cases, parts are already quite compassionate and cooperative, which makes work on traumatic memories more simple and straightforward, and they may become one (integrate) during or shortly after that work is done. But most patients have a much longer road to integration, well into Phase 3. Most commonly, parts gradually merge over time in a naturalistic way.

Like fusions, unification may occur spontaneously or be more gradual in various patients (Kluft, 1993b). Some patients see it as an important milestone; others take it in stride as though it is expected; and a few avoid it even when they are ready, due to a phobia of fusion. Some patients recognize the time has come for unification; others are surprised by it. Some experience it as a loss or death or sad leave-taking. Others see it as a joyful celebration, a sign of success and mastery. Each patient will approach unification differently, and the therapist must understand and help the patient through in the patient’s unique way.

Steele, K., Boon, S., & Van Der Hart, O. (2016). Treating Trauma-Related Dissociation: A Practical, Integrative Approach (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). W. W. Norton & Company.

—47

Trauma is not just a ‘bad experience’ that I haven’t been able to get over. Chronic trauma in childhood is a way of life and a way of learning. It defines the way that our brains organise and understand information. Recovery is a slow, hard process, and it cannot be achieved in six sessions or even six months. Because trauma by its very nature is disintegrative, disconnecting and disempowering.

Trauma breaks down the normal integration, the normal joining-up of thoughts, memories, feelings, behaviours, perceptions and sensations. Our memories are disjointed and held as somatosensory fragments. Our feelings don’t integrate with our memories. Our thoughts don’t integrate with our behaviours. And trauma has a profound effect on our autobiographical sense of self, as we see in my own experience of dissociative identity disorder (DID). I grew up without an integrated sense of self: all the different aspects of my experience and my self-identity did not join up together into a coherent whole. So I developed with what is vividly but inaccurately described as ‘multiple personalities’. Walt Whitman, the American poet, expressed it well—he said, ‘I am large; I contain multitudes.’

Spring, Carolyn. (2016). Recovery is my best revenge: My experience of trauma, abuse and dissociative identity disorder (pp. 185-186). Carolyn Spring Publishing. Edición de Kindle.

—48

Sarah spoke about her internal parts in terms of integration.

I don’t feel as segmented as I used to, but in the process, we have all become one in the sense that we agree on things together, and we don’t move forward until we’re all together. And we move forward a lot, and we are ready to keep moving and growing…all of that. None of them didn’t want to, and as they started to understand and cooperate and feel nurtured, the more nurtured they felt, the more I came together, just parts of me.

So now we are individualized and still think separately. I’ll tell you about reading this paper [the interview guide questions] and M.’s ideas are very distinctive, and they come through very clearly. We work together better, and we’re like a team, and I feel stronger and more whole. The parts of me, it’s like I’m more than one person, that’s how strong I am. I’m a force to be reckoned with—in a good way. And I acknowledge that I have nurtured and developed each piece of me to a point of being healed and happy, and I don’t want union [integration of personality], that’s just how it happened for me.

…

This was not about integration as defined by the mental health professional or in the professional literature. The women were referring to a conscious connection, respect, and cooperation within themselves as it happened within their therapy and then generalized to other relationships. They chose to retain their internal systems, adjusting the internal relationships to maintain adaptive functioning in their lives.

Green, PhD, LCMHC, MA, NCC, DCC,, Elizabeth. Our Voices: Six Women With Multiple Personalities Talk About Life and Relationships in Their Midlife (pp. 44-45). Edición de Kindle.

—49

JENI

A major thing George did help me with was MPD integration. My mind was split into fragments that were beautifully organised, but they didn’t come together to form a complete jigsaw puzzle. The goal was to fuse my alters together to become a unified whole, so I could function as one person. The treatment wasn’t about getting rid of alters or switching them off, it was about combining them in harmony. To do that, Erik asked each alter to find a buddy who complemented their skills so they could merge. This process was more than just a blending of the minds. It was a process of each pairing finding a common ground and creating mutuality. They would find something in common, spend time working together, sharing tasks and developing ways to best communicate with each other. When the two were comfortable with being together, they would create a space where they could work simultaneously. Finally, when they were ready, two would become one. For example, the Laughing Man (whose strength was his ability to laugh in Dad’s face) merged with The Joker (who found the humour in every situation). Working with George we created integration ceremonies to help this process. Once we understood the importance of carrying out integration ceremonies, we created one that we could use outside of the therapy hour, and without George’s help.

Haynes, Jeni; Blair-West, George. The Girl in the Green Dress (pp. 374-375). (2022) Hachette Australia. Edición de Kindle.

—50

In the bathroom that night, someone lettered in a childish scrawl, with a lipstick on the side of the claw-legged tub, “Two, four, six, eight, we don’t wanna integrate!”

“Stanley is a mean man,” Lamb Chop told the woman later. “He wants to kill us.”

“That’s not what integration means. . . .” The woman couldn’t finish the sentence. What did integration mean for them all? They were individuals, no two alike.

…

They offer a new option for resolution. After I became aware of the multiple persons I fully expected that the goal of psychotherapy would be to find the central person and to integrate the others into the process of that one. However, I discovered that the “core” was dead, and that the process of healing would most likely result in a number of persons who spoke through the “shell” of a woman. The task became cooperation of many, rather than the integration into one. This book has been the result of that cooperation and demonstrates the efficacy of this means of resolution. Increasingly, therapists who work with multiple personalities report more than one type of resolution. In the case of the Troops the first-born is dead and the decision is to maintain multiplicity. The developing resolution for the Troops has meant increasing awareness of each other and a sharing of those important and traumatic experiences that resulted in the development of multiple persons. Communication among the Troop members has been enhanced, and there is evidence of an increased ability to cooperate and work together. This book became both the catalyst and the vehicle for encouraging healthier working relationships among Troop members.

Chase, Truddi. When Rabbit Howls (1990) Penguin Publishing Group. Edición de Kindle (p. 364).

—51

Note from Dr. Steve Clancy

My first session with Leah felt a little bit rushed to me. She announced that she was multiple, told me some about her inner world (i.e., names, ages and functions), and told me she/they were ready to integrate. I must admit that my past experience working with people with DID followed a somewhat different pattern. Usually, after a couple or more years of therapy, testing (of me), trust building, catastrophe and catharsis, the decision to integrate was finally broached, then negotiated, and finally completed. To have someone walk into a first session and say they just wanted a little help integrating was a shocker. But, Leah meant it. And, of course, for her it was not a quick decision. She had worked with other therapists in California, she had written a good portion of this book and she had used her art for years as an integral part of her therapy.

Even so, we did work fast and effectively. Introductions were made, fears were laid to rest and integration proceeded smoothly. While our relationship was brief and her final integration unusual (in that I was very new to her life and system), her story in many ways was not unusual at all. At the heart of it was a deep sense of shame. A shame of such monumental proportions that it must be hidden. Secrets of shameful events were guarded and kept under wraps. Whenever the mind resorts to such creative but extreme measures as the making of alter-personalities, one finds secrets so shameful that the rage naturally engendered by such events is disguised and displaced. In every case you will find a «Samson» or a father (or some other powerful, significant adult) who does «things» to a child that simply cannot be talked about. These things must be hidden or denied or distorted.

Peterson Crawford, Leah.(2005) Not Otherwise Specified: a multiple life in one body, 15 year anniversary edition. Edición de Kindle.

—52

Un día me di cuenta de que cada vez que me encontraba con Jan, mi cabeza se sentía aturdida. Si ella se dirigía a mí, me sentía aún más ansiosa y ofuscada, como si mi cabeza se llenara de algodón. Perdía la capacidad de pensar con claridad. Me había estado disociando toda la vida, pero esta era una de las primeras veces en que lograba identificar que me estaba pasando, fuera de la oficina del Dr. Summer. Estaba tan acostumbrada a sentirme aturdida y adormecida que era difícil detectarlo; sentirme así siempre era un impedimento para reconocer que estaba sintiéndome de esta manera. Pero como había integrado más partes, esto me había empezado a permitir volverme más enfocada y tener más claridad. Cuanto más me integraba, más aguda se sentía mi mente. Me encantaba esta sensación de claridad y quería más.

—53

I read the letter over several times. Holdon has given me a step-by-step procedure for Karen’s integration. I am utterly amazed. Could it work? This is similar to the fusion rituals Putnam described in his book Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Personality Disorder. I didn’t really understand what he was talking about at the time; it was a bit vague. It’s also a little scary. We’ve been gradually dissolving the separation between the alters, but this is an all-at-once, wholesale integration of an alter. I can’t imagine what will happen. Fortunately, this plan shouldn’t be too hard to sell to the alters since it comes from Holdon.

Baer, Richard.(2007) Switching Time. A Doctor’s Harrowing Story of Treating a Woman with 17 Personalities.

—54

4. Copresence is the ability to coexist with another personality—sort of sharing the driver’s seat! In this situation, the alters are cocognizant and are separate personalities who can confer back and forth and decide a course of action. Copresence usually happens before fusion or integration. Before the host reaches this stage with any of the alters, she can know about the alters only through her therapist.

…

A motley crew as individuals yesterday, they lend a rich dimension to her life in terms of skills, emotions, and knowledge now that they are integrated and fused with Helen’s personality. She had one relapse—six months after fusion when her sister died in a terrible car accident—but after another year of therapy, Helen’s integration held, and she was pronounced successfully fused.

—55

On rare occasion, I think that I have seen MPD patients who were multiples in childhood and achieved a spontaneous fusion during late childhood or early adolescence ( or at least the complete suppression of other alters), and who then experience the appearance of separate alters during adulthood in association with severe life stress.

…

This technique will move the therapist around within the personality system and fill in some of the gaps. The therapist should not expect to meet them all on the first pass; chances are that new alters will continue to emerge up to the final fusion.

…

In later stages of therapy, when there is some acceptance of the diagnosis, MPD patients often become hypergraphic and bury the therapist with lengthy excerpts of autobiographical writings. In some cases, these autobiographies become important projects that unite the alters around a common theme and serve as a focus of internal collaboration and self-revelation. Each alter can add his or her piece to the puzzle, and each can come to know the others through their contributions. The patient first assembles himself or herself on paper as preparation for fusion and integration. Abreactions may accompany the recording of some past experiences, but many patients learn to take this in stride and use it as a technique to continue the work outside of the treatment setting.

Putnam, F. W. (1989). Diagnosis and treatment of multiple personality disorder. Guilford Press.

—56

Sometimes » It,» as Sally humorously called her, was distinctly B I or distinctly ‘IV ; I more or less modified, but with the memories of both. At such times the fusion of memories was not always complete. that is, it did not include the whole life of B I and B IV, but only specific events or periods of time.

…

The greatest tranquillity and stability followed the complete fusion of I and IV, and then the resulting *’ New Miss Beauchamp » would enjoy several days or a week of peaceful life and strength.

…

On several occasions, however, a personality was obtained who exhibited all the evidences of a perfect fusion of the two personalities. She remembered her life as I and as IV.

Prince, M. (1905). The dissociation of a personality.

—57

The goal of most therapy with multiples is an integration or fusion of the separate selves, resulting in a single, normally unified whole. At what point in the dynamic progression toward this state of unified awareness are we to say that the description of multiplicity ceases to apply? When do several separate selves reduce, by elimination or integration, to one self, with at most separate aspects or dimensions? This determination will rest at least in part on how the disordered-awareness condition is understood.

…

An attitudinal readjustment is also required over past wrong perpetrated by one or another self. Here, though, the newly minted unified self must differentiate finely, as Putnam makes clear in these remarks:

Typically, while a multiple, the patient assumed responsibility for much of the trauma that was inflicted upon him or her, over which the patient actually had little control. Paradoxically, while still a multiple, the patient often ignored responsibility for his or her own hurtful or harmful actions toward others. Following fusion, these discrepancies must be reversed. Accepting responsibility for his or her actions is often extremely painful for the patient to face. . . . While assuming this responsibility the patient must be consoled and supported by the therapist and helped to understand that he or she was ill and often reflexively inflicted upon others what had originally been done to him or her. (1989, 319)

Radden, J. (1996). Divided minds and successive selves: Ethical Issues in Disorders of Identity and Personality. MIT Press.

—58

The most common reasons for the hospitalization of MPD patients include suicidal impulses and attempts, self-inflicted injury of a nonsuicidal variety, depression, and threats of violence. «Most admissions of known MPD patients occur in connection with (1) suicidal behaviors or impulses; (2) severe anxiety or depression related to reemergence of upsetting alters, or failure of a fusion; (3) fugue behaviors; (4) inappropriate behaviors of alters (including involuntary commitments for violence); (5) in connection with procedures or events in therapy during which a structured and protected environment is desirable; and (6) when logistic factors preclude outpatient care.»

…

The sixth stage, integration/resolution, involves the coming together or at least the achieving of reconciliation, cooperation, and coordination among the alters. Integration and fusion often are used as synonyms, because both refer to the unification of the alters. In more specialized MPD literature, however, integration actually refers to an ongoing process of undoing all aspects of dissociative dividedness. It begins long before there is any reduction in the number and distinctness of the alters, continues through their unification, and continues at a deeper level even after the personalities have blended. Fusion indicates the moment when alters can be considered to have ceded their separateness.

Kluft RP. Hospital treatment of multiple personality disorder. An overview. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1991 Sep;14(3):695-719. PMID: 1946031.

—59

When personalities that were close to one another had processed their experiences, they tended to begin to integrate into one another and into Carole herself. Sometimes they blended spontaneously, but others required hypnotic suggestions (using imagery of joining) to integrate.

…

Some DID patients’ alters integrate one by one or in small groups, whereas others’ alters remain separate until all or almost all are ready to join together. In Carole’s case, there was no spontaneous integration until the material concerning her mother was processed.

Spitzer, R. L. (2006). DSM-IV-TR Case Book Vol.2: Experts tell how they treated their own patients. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub

—60

Situation 14: Some parts of me (e.g., the host personality, or the

little one) disappear. What’s going on?As long as a part of the personality forms, it never truly disappears. It may hide, it may be unavailable, it may be suppressed, or it may fuse together with some other parts. Even in the context of DID, a dissociated personality state will not truly ‘die’, ‘disappear’ or be eliminated. A part may ‘disappear’ willingly or unwillingly. You need to try to understand the reasons behind this. If it is really the choice of that part, you may need to respect the decision. Try to maintain communication (no matter if they are here to listen or not – it is always possible for them to receive your messages even if they do not appear to be here), give a hand to your internal teammates, and see what they need.

Fung, H. W. (2019). Be a Teammate with Yourself: Understanding Trauma and Dissociation. Manitou Communications

—61

An alter that is believed to have ceased being separate is considered »apparently fused.» However, many apparent fusions do not hold; rapid relapses are common. Any alter, or the patient as a whole, actually should not be considered to have fused until there have been 3 stable months of the fallowing:

1. Continuity of contemporary memory;

2. Absence of overt behavioral signs of MPD;

3. Subjective sense of unity;

4. An absence of alters (or the particular alter) on reexploration (preferably involving hypnotic inquiry);

5. Modification of the transference phenomena consistent with the bringing together of the personalities; and

6. Clinical evidence that the unified patient’s self-representation includes acknowledgment of attitudes and awarenesses that previously were segregated in separate personalities.When these criteria have been fulfilled for 2 years after the 3

months, one can use the term »stable fusion.»

Kluft, R. P. (1993). Clinical Perspectives on Multiple Personality Disorder. American Psychiatric Pub.

—62

Whenever possible, I have found it wisest to let the child be in charge of timing and which personalities fuse or integrate first. As memory work and abreaction progress, some of the child’s parts may want to fuse fairly quickly. This can happen especially if one part’s work is finished, if the role that part played or the service it performed for the child no longer needs to be kept separate (Dell & Eisenhower, 1990)…. The personality may then be ready to integrate, along with the once dissociated information. This may not always be true, however; some parts do stick around to help out in other ways, especially if their role is to be protective.

The fusion of two personalities can often have immediate positive effects. April’s first fusion was judiciously chosen as to timing and parts involved. One part carried a lot of feelings; the other part could verbalize the feelings and ask to get her needs met. The fusion of these two parts produced one who could do all of these functions without switching. The choice of which parts to fuse first was made by April herself; I couldn’t have made a better one.

…

It is also possible for two parts that have fused to reseparate. This can happen if the two parts were not really willing and prepared to join, or if an overwhelmingly stressful event (such as being reabused) occurs shortly after the fusion, requiring the child to resplit in order to cope. Usually, if the fusion lasts several weeks, it will continue to hold.

Shirar, L. (1996). Dissociative children: Bridging the Inner and Outer Worlds. W. W. Norton.

—63

Although much of the writing on DID suggests that the goal of therapy is to integrate the alters into a unitary personality, that was never my goal. My approach was to help them become, as Putnam recommends, a full functioning unit. If the alters are fused into one personality, there is the risk that without their main defense— disassociation—integrated patients may lack sufficient protection against the ordinary stresses of life, and thus subject to splitting again in the future. This is particularly a risk should a subsequent stressor have anything in common, by word, deed or other trigger, with prior traumas.

Yeung, D. (2014). Engaging multiple personalities. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform.

—64

In this system, all the antisocial, acting-out personalities were in one community, whereas the other community prided itself on ‘‘never causing any trouble.”” Although there were no switching rules in this system, the sequence of integrations was highly structured. Sisters were integrated first; the products of the integration of sisters were then fused so that an entire family was integrated; families were then integrated until there was only one personality plus the Observer in each community; the Observers were then integrated with their respective personalities; finally the two personalities representing each community were integrated. The patient would not allow fusions to be attempted out of sequence and said they would not work.

Ross, C. A. (1989). Multiple Personality disorder: Diagnosis, Clinical Features, and Treatment. Wiley-Interscience.

—65

In the DID literature, this type of intervention is viewed as an adjunctive technique to facilitate unification of DID alternate identities (ISSTD, 2011; Kluft, 1982). Further, this sort of intervention should only be used in the context of wellconstructed phasic treatment of DID. It can be harmful to use this type imagery without sufficient preparation and informed consent for patients to integrate self-states (Kluft, 1993).

Brand, Bethany & Loewenstein, Richard & Spiegel, David. (2014). Dispelling Myths About Dissociative Identity Disorder Treatment: An Empirically Based Approach. Psychiatry. 77. 169-89. 10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.169.

—66

Whether a DID patient is ultimately a candidate for full integration (i.e. whether integration is a realistic therapeutic goal) will depend predominantly on the patient’s capacity for processing traumatic material. Only a minority of DID patients achieve full integration, thus care must be taken in determining whether treatment should proceed with that aim or if a patient would benefit more from supportive treatment. For those DID patients who are not candidates for definitive treatment, significant therapeutic achievements are still feasible, such as greater distress tolerance, maintenance or improvement in functional status, as well as more adaptive communication and collaboration between alternate identities.

Tohid, H., & Rutkofsky, I. H. (2024). Dissociative Identity Disorder: Treatment and Management. Springer Nature International Publishing.

—67

These wrong diagnoses then deny the patient the opportunity for an uncovering psychotherapy that would access and abreact their horrendous histories, repressed feelings, and tissue memories. The process of this type of psy.chotherapy facilitates internal understanding and leads to the breakdown of the amnestic barriers and ultimately to integration and unification of the multiple personality system. MPD is a hopeful diagnosis of a treatable condition and it is a privilege to be a witness, as a therapist, to this healing journey, especially with a patient who was chronically disabled and who becomes totally functional.

Cohen, L. M., Berzoff, J., & Elin, M. R. (1995). Dissociative Identity Disorder: theoretical and treatment controversies.

—68